Each February, the NFL world is set ablaze with wall-to-wall coverage of the NFL Scouting Combine. This provides us with endless opportunities to define a prospect’s future based on how he looks in underwear — long before the actual professionals employed by teams get to weigh in on NFL Draft night.

This naturally leads me to wonder: does the Combine tell us anything above and beyond what teams naturally tell us by where they choose to draft each prospect two months later?

We might think of this question in terms of two possible worlds. Is strong athletic testing itself an indicator a player will succeed? Or does it only hint toward draft capital — which is what truly holds all of the power to predict production?

In the first world, a prospect’s athleticism should be a durable piece of our evaluation even after we learn how highly the NFL drafts them. In the second world, the Combine would still be useful at helping us guess what NFL teams will do, but we should largely forget whatever happened at it once teams show their hand — “trusting” the NFL to evaluate athleticism for us.

In trying to find out which world we live in, I updated Scott Barrett’s SPORQ athleticism model to incorporate all of the most predictive athletic measurables at each position over the past 24 years into a single composite athleticism score. I outline the metrics, adjustments, and archetype groupings the model includes within the Index section at the bottom of this piece. All SPORQ ratings can be accessed here.

Running Backs

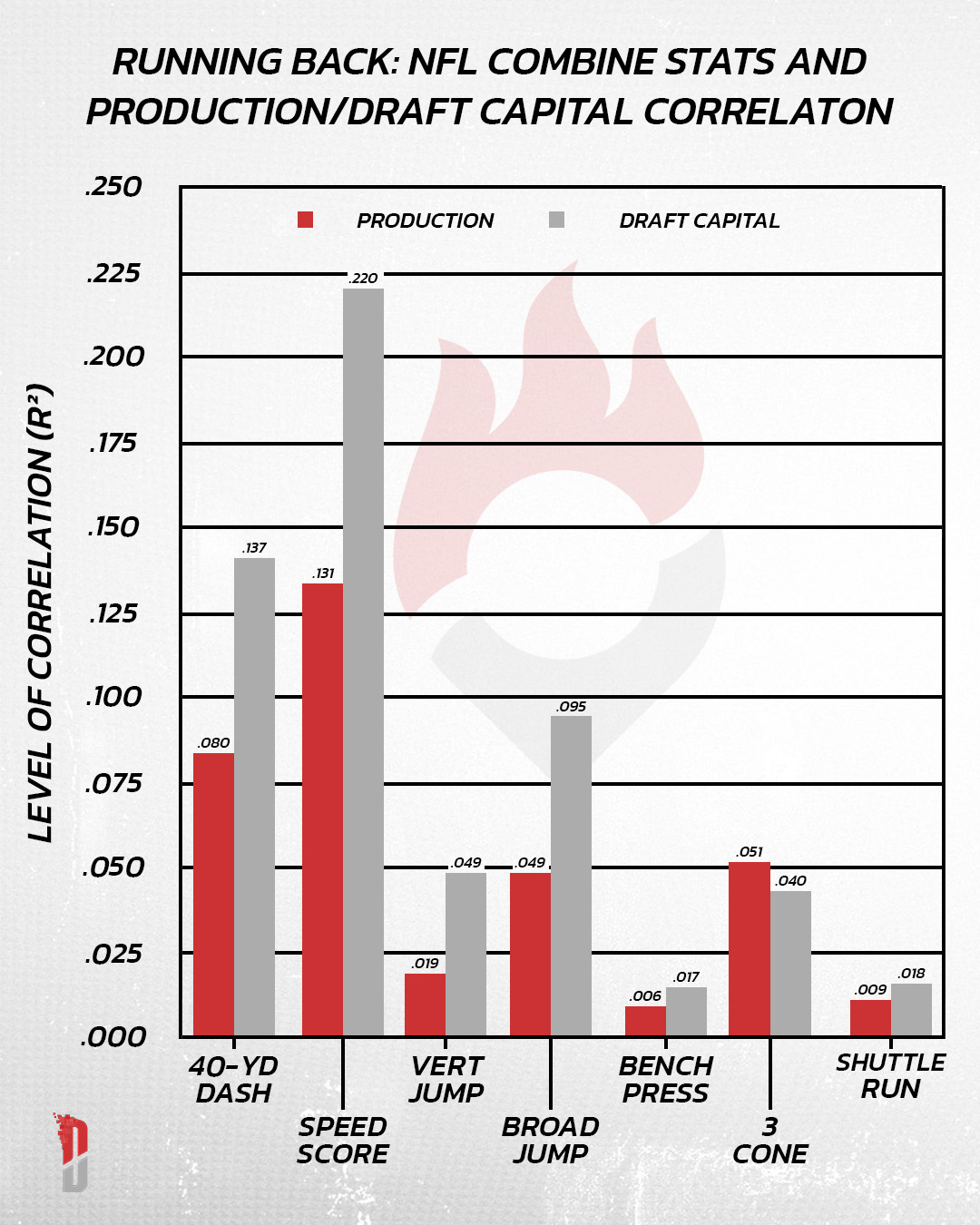

We can start by determining how predictive of production (for our purposes, early-career fantasy production) each Combine event is. Then, we can layer in how well each event predicts a player’s NFL Draft position using the Fitzgerald-Spielberger draft value chart, borrowing from Tej Seth’s research.

While straight-line speed — especially when weight-adjusted like Bill Barnwell’s speed score[1] — is the athletic trait most predictive of fantasy production, NFL teams still overvalue it when deciding which RBs to draft. We can say something similar for each of the main Combine events aside from the 3-cone, which seems uniquely underrated. For example, Christian McCaffrey has the best weight-adjusted 3-cone time this century.[2]

Athleticism is largely overrated by both teams and fantasy managers. But that doesn’t necessarily mean we should ignore the Combine. There’s something more interesting going on here. It begins with the understanding that draft capital and production are not independent of each other.

Teams tend to give opportunities and playing time to RBs on whom they’ve spent significant resources. In fact, draft capital can be better at predicting future fantasy production than a season of an RB’s actual fantasy production. All else equal (whether the all else be athleticism, skill, or any other trait), a higher-drafted RB will have more chances to see the field and score fantasy points early in his career than a lower-drafted RB. Snaps are massively predictive of fantasy scoring at the RB position.

For all of these reasons, I believe that all prospect analysis should either incorporate draft capital or make specific attempts to identify holes within it. Now we can answer our central question — whether NFL teams already squeeze out the entire edge in evaluating athleticism for us — by bucketing RBs based on their SPORQ athleticism ratings and NFL Draft position.

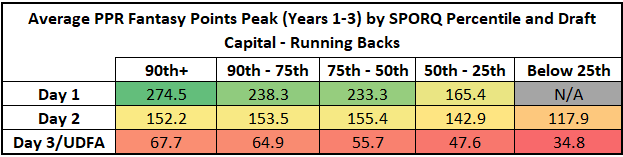

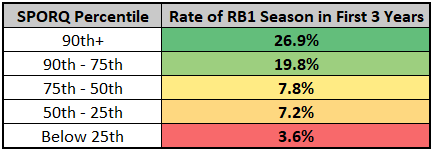

As it turns out, the RB position resides in a combination of our two hypothesized worlds. Draft capital is highly predictive of early-career production regardless of athleticism, but SPORQ is still useful at predicting which RBs will be productive within those draft capital buckets.

This is especially true at the extremes.[3] Among RBs taken in Round 1, 90th-percentile and above athletes average ~66% more peak production than those in the 50th-percentile and below. Draft analysts and fantasy managers should continue to keep an RB’s athletic testing in mind even after NFL teams reveal their evaluation via the Draft.

Teams almost never draft sub-par athletes on Day 1[4], but within Days 2 and 3, RBs ranking below the 25th percentile in athleticism can be expected to produce less than their more athletic but similarly drafted counterparts. There are still under-athletic hits on Day 3 — Kyren Williams and Bucky Irving[5] being recent outlier examples — but as a general rule, failing to meet a minimum threshold of athleticism spells trouble for RB prospects regardless of where they’re drafted.

In fact, dynasty managers who want to maximize their chances of selecting a rookie capable of posting an RB1-level season early on in their careers should focus their player pool on RBs that test as at least 75th-percentile athletes. As we’ve discussed, some of this effect is also a result of highly athletic RBs being drafted higher and therefore seeing the field sooner, but athleticism on its own merits remains an important piece of the puzzle.

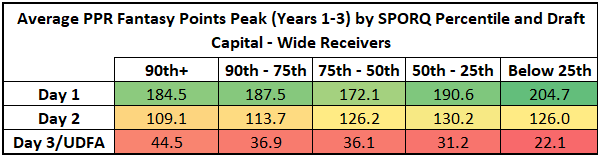

Wide Receivers

Even before I ran the numbers at WR, I could have told you that teams are incomprehensibly obsessed with over-drafting speed at the expense of almost everything else.

The Top-30 Fastest Wide Receivers in NFL Combine History

— Scott Barrett (@ScottBarrettDFB) February 15, 2025

Round 1 picks: 8

Round 1-3 picks: 27

1,000-yard WRs: 1

DUI Manslaughter: 2 pic.twitter.com/vp4rI3vsPV

To that point, notice that 24 of the 30-fastest WRs (80%) on the above list measured at under 73 inches (compared to 45% of all of the position’s 40-yard dash participants within my database). It makes sense that smaller players would be overrepresented on this list; it’s easier to move fast if you have less mass.

This is the reasoning behind metrics like speed score (weight-adjusted), and it’s why we’ll be treating short and tall receivers differently in our model (height-adjusted). Different physical traits are predictive of on-field success within each archetype (explained in detail in the Index at the bottom of this piece) — a player built like Cole Beasley likely won’t win as a contested-catch artist, and vice versa. And just as importantly, NFL teams treat these players differently when deciding where and how early to draft them.[6]

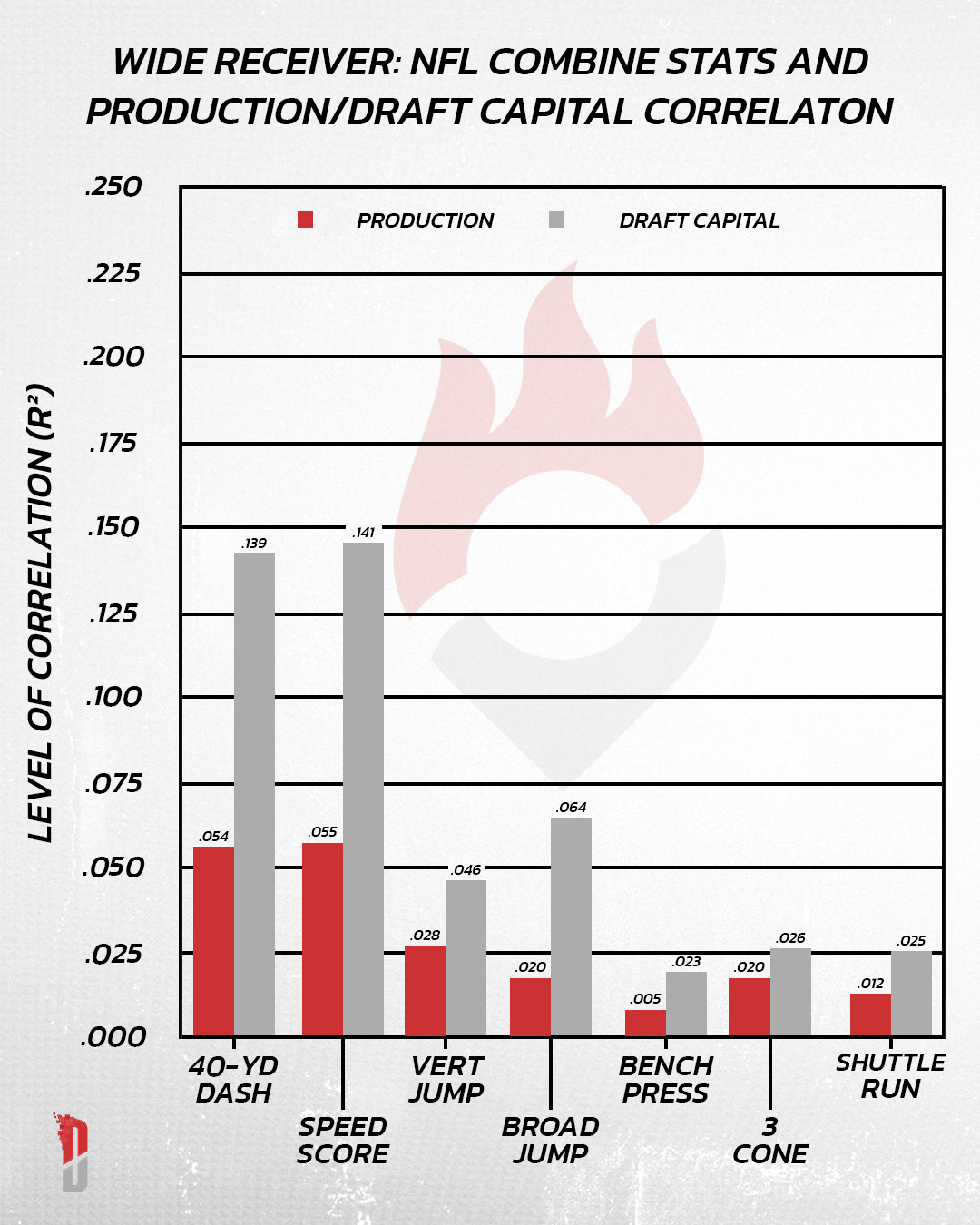

But even if we zoom out from how size complicates things, teams massively overrate all manner of athletic testing at the WR position, full stop. This is apparent from observing how much better each Combine event predicts draft capital than production.

This creates a problem for the model regardless of whatever adjustments I attempt to make. Teams so heavily overvalue athleticism at the WR position — to the detriment of other more important traits and football skills — that it’s actually a slightly negative predictor of production after we control for draft capital.

In other words, the more athletic a Day 1 WR is, the more he will lack other important traits (route running prowess, separation ability, etc.) on average. NFL teams pull qualitatively worse WRs into higher rounds if they are athletic enough. And because teams cannot as easily force volume and production to lesser-skilled but highly-drafted WRs as they can to RBs (since they still have to get open and earn a target, no matter how often they’re on the field), it results in less athletic (and therefore more skilled overall) WRs outproducing their highly-athletic counterparts.

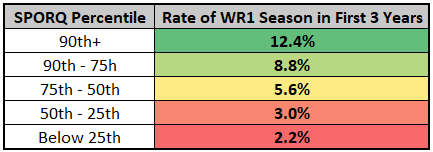

This isn’t a new idea — as usual, there’s an Adam Harstad DM from years ago explaining “Berkson’s Paradox” perfectly — but the graphic above drives home that analysts and fantasy managers should largely disregard Combine measurables for WRs the moment NFL teams have weighed in with their thoughts. WRs live entirely within the second world we hypothesized earlier: whatever helpful information athletic testing can give us, it’s entirely subsumed by draft capital.

That’s not to say my WR SPORQ model is useless — just that most of its power actually rests in predicting which WRs teams will likely draft higher. Still, receivers' chances of a WR1-level season fall off sharply the worse they score in it. Also, remember that we’re only looking at the top tier of overall human athleticism; truly “unathletic” players will never be drafted by the NFL or invited to the Combine in the first place, so their poor hit rates don’t have a chance to show up here.

Tight Ends

Raw athleticism is massively important for TEs. A range of backgrounds, from college QBs to former basketball players, have found success here.

There’s a common belief that the TE position’s learning curve is especially steep, but that isn’t as borne out in the data as you probably think: ~59% of elite TEs (compared to ~44% of elite WRs) have broken out within their first two seasons in the NFL. Players like Darren Waller, Antonio Gates, and Jimmy Graham broke out nearly immediately after converting to the position, further proving the importance of the rule of hyper-athleticism.

Also, the need for a successful fantasy TE to excel in only one of the position’s two main jobs (receiving rather than blocking) may further contribute to the success of raw athletes. To calibrate toward fantasy relevance, we’ll focus our analysis below on TEs weighing in at 265 or fewer pounds.[7] I still included heavier TEs within the SPORQ model with significant adjustments (again, all explained in the Index).

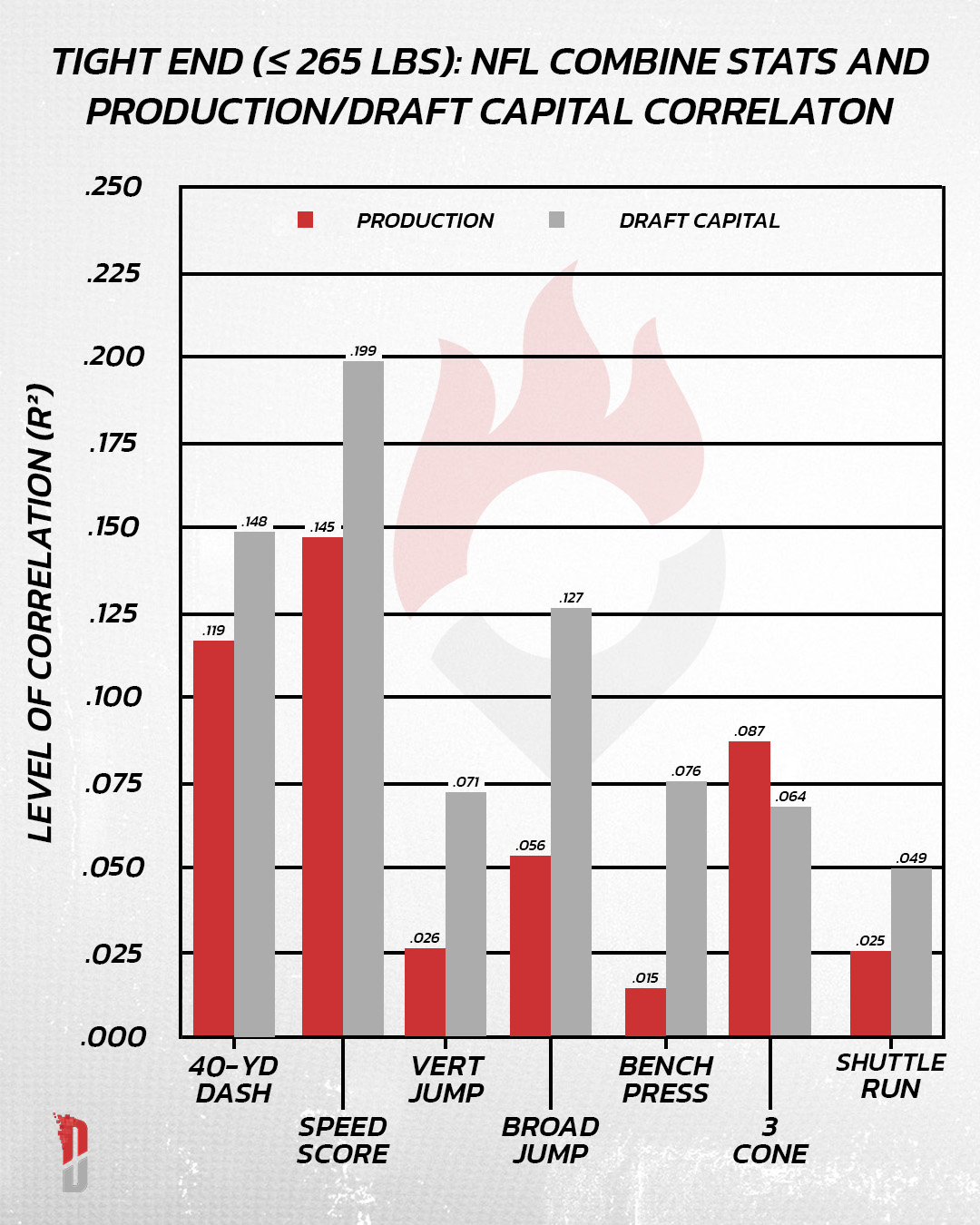

Similar to other positions, NFL teams place more faith in TE athletic measurables than they are individually predictive of production. However, we do see better predictiveness across the board at TE than at RB or WR, and the 3-cone drill again seems undervalued by teams, especially after weight adjustment.[8]

Also of note is that both the Vertical and Broad Jump (often collectively referred to as the “burst” events, as they combine to make up the relatively popular “burst score”) are likely overrated[9] by the analytics community. It’s apparent from the chart above that each is inferior to the 40-yard dash and the 3-cone for predicting production.[10]

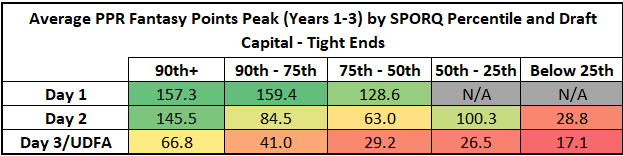

Despite teams still overvaluing most individual measurables when they draft TEs, these quirks and inefficiencies create space for the SPORQ model to augment our analysis, even above and beyond what draft capital tells us. In other words, TEs exist mostly within the first world we hypothesized; their athletic testing can help tell us their destiny, independent of what NFL teams think.

Observe below that highly athletic TEs falling to Day 2 perform nearly as well as those taken in Round 1.

Several of the “hits” from that highly athletic Day 2 group (Sam LaPorta being a recent example) excelled in the weight-adjusted 3-cone. Others (Jason Witten, Travis Kelce, and Rob Gronkowski) made it in due to their excellent speed scores. If any of 2025’s crop of TEs slip to Day 2 despite performing exceptionally well in one or both of these drills, I am going to target them heavily in rookie drafts.

We can also see that athleticism remains important on both Day 1 and Day 3. George Kittle posted the best SPORQ score of any TE in our database and became the position’s biggest Day 3 steal this century. And TEs taken in Round 1 who lack 75th-percentile or better athleticism can be expected to produce less than those who do possess it.[11]

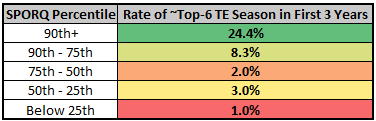

And remarkably, even from a “draft capital blind” perspective, nearly 44% of TEs who grade out as 90th-percentile or better SPORQ athletes have posted a TE1-level fantasy season within their first three years.[12]

In contrast, only one of 242 TEs ranking below the 60th percentile in SPORQ have ever posted a 1,000-yard season: Zach Ertz.[13] For that reason, I’ll be the most hyper-focused on the TE position when the NFL Combine begins in a few days.

TL;DR

Does the Combine tell us anything above and beyond what teams naturally tell us by where they choose to draft each prospect two months later?

For RBs, incorporating Combine measurables within our fantasy analysis is an advantage even beyond what NFL teams tell us via draft capital — though mostly at the extreme top and bottom ends of the athleticism spectrum.

For WRs, the edge is actually in ignoring the Combine entirely once a WR has been drafted. NFL teams so overrate athleticism at the position — at the expense of more important traits — that it creates a negative relationship between athleticism and fantasy production within each draft round.

For TEs, athleticism is massively important, and there is an enduring edge in considering it even after the NFL Draft. Uber-elite athletes at the position can overcome lower draft capital, and high draft capital won’t save sub-elite athletes as often.

Index: SPORQ Model Explanation

SPORQ uses measurable attributes alone to predict a player’s best season within the first three years of their career, as measured by PPR fantasy points. This is both a solid measure of on-field production and a close proxy for a player’s peak value in dynasty formats, as most breakouts occur within the first three seasons. (Even if a player breaks out later than that, we’ve by that point had ample opportunity to see their play on an NFL field and acquire them at similar or lower prices in dynasty leagues, reducing my desire to account for later breakouts in my prospect evaluations.)

In all cases, a player must run the 40-yard dash (the most predictive event, even if teams and the public overrate it) to qualify for the model. Heavy TEs (above 265 pounds) must also have participated in the vertical jump to qualify. The model utilizes NFL Scouting Combine data since the year 2000.

Running Back

Speed score (a weight-adjusted 40-yard dash metric invented and popularized by Bill Barnwell) is weighted the heaviest.

I found that BMI-adjusting the broad jump and weight-adjusting the 3-cone drill improved their predictiveness, so I also included these within the model.

However, the 3-cone seemed to matter less for RBs with especially heavier builds (think of Derrick Henry and Brandon Jacobs), so I made special adjustments there as well.

I also wanted to reward RBs for excelling at several different events. I’m of two minds on this — players often avoid running events they’ll perform poorly in, but they also often skip events if they know they’ll be drafted highly anyway, which suggests they’ll be productive in the NFL — but in this case, I settled on including penalties for skipping multiple events, and adding slight bonuses for excelling in the vertical or bench press.

The overwhelming majority of successful RBs have weighed between 197 and 247 pounds. I penalize players who fall outside of this range. Offensive skill position players are generally getting lighter in recent years, so I wanted to be relatively loose and forgiving here.

But I also don’t want to understate the importance of size at the RB position. Coaches are reluctant to give bell cow workloads to undersized players, and volume is almost all that matters for fantasy football. NFL history is littered with undersized backs who post gaudy efficiency metrics but never receive full workloads; it’s why nearly everything in the RB SPORQ model is weight or BMI-adjusted in some way. Only 3 of 71 RBs weighing below 195 pounds in our database exceeded 250 PPR fantasy points in any of their first three seasons (though Kyren Williams and De’Von Achane recently joined this exclusive group).

Wide Receiver

Since NFL teams treat tall and short receivers differently (discussed above), my model should as well. I split receivers into two buckets: “short” (below 73 inches) and “tall” (73 or more inches).

For the tall group, I found speed score and a height-adjusted version of the broad jump to be most predictive. These are weighted the heaviest.

Among the short group, adjusting the 40-yard dash for both height and weight (rather than only weight, as speed score does) yielded better results. I also found a weight-adjusted version of the 3-cone drill to be worth including for this archetype.[14]

The vertical jump retained importance among both groups. But I included an additional bonus for shorter receivers with especially impressive verticals—teams seem to recognize that jumping abilities can compensate for smaller statures.

Finally, receivers below a 24.0 BMI and/or shorter than 5’10’’ received penalties.

Tight Ends

Tight ends above 265 pounds almost never end up as receiving threats in the NFL, so I’ve split them into two groups (heavy and light) within the model. Since we’re targeting fantasy production, the heavy group gets a significant dock off the bat.

But I also penalize TEs for being too small, as there does seem to be a sweet spot in terms of size. Being shorter than 6’3’’ or lighter than ~230 pounds lowers a TE’s hit rate significantly. There’s a school of thought that the smaller and more like a WR a TE is, the better for fantasy football, but aside from this counterpoint about teams increasingly requiring blocking skills from TEs for them to get on the field, I’d ask: “why aren’t they just a WR, then?” It’s probably because they can’t beat CBs, implying they aren’t particularly great “receivers” in the first place, and aren’t big or quick enough to be effective mismatches against LBs or safeties.

For lighter TEs, speed score, weight-adjusted 3-cone, and the broad jump were most predictive. They’re weighted in that order.

For the heavier TEs, the vertical and the shuttle were the most predictive, so they are heavily weighted within that archetype.

Finally, even lighter TEs seemed to especially struggle if they failed to hit a minimum threshold on the shuttle, so I included a minor penalty to reflect this.

Footnotes

The speed score formula is: (Weight x 200) / (40-yard dash time ^ 4)

Le’Veon Bell, Ray Rice, David Johnson, Doug Martin, and LeGarrette Blount joined McCaffrey within the top-25 best weight-adjusted 3-cone times. Of that group, only Martin and Johnson boasted elite testing in other areas. Naturally, I’ve included this metric within the updated SPORQ model.

Data can often appear near-useless in the aggregate, but be absolutely critical at the extremes. A power-law distribution rules fantasy football and is fundamentally about finding outlier talents and situations that can near-singlehandedly win you a league. There may be little or no functional difference between a 60th and 40th-percentile SPORQ athlete (as the entire group is only made up of human beings who were athletic enough to be invited to the NFL Scouting Combine), but a 99th-percentile athlete does have a noticeable advantage over a 10th-percentile one (confirmed by the drafting behavior of NFL teams). In other words, the predictive power of the SPORQ model may not be evenly distributed when we’re already dealing with only the 99th+ percentile of human athletic achievement.

Out of 10 RBs drafted in Round 1 ranking below the 70th percentile in SPORQ, only C.J. Spiller and Shaun Alexander reached 1,000 rushing yards within any of their first three seasons. Clyde Edwards-Helaire was the most notable recent bust from this group.

Irving was an otherwise flawless prospect if not for height, weight, and athleticism. For those curious, he and Williams are the only RBs in my database below a 5th-percentile SPORQ score to have ever posted a 1,000-yard season. And that pair ranks as two of the five highest-drafted players within that group (the others were Ronald Jones, Donnel Pumphrey, and Jacquizz Rodgers).

If we split WRs into these two archetypes — “short” (sub-73 inches) and “tall” (73 inches and above), it becomes clear that teams are making size-related mistakes in their evaluations. As we’ve discussed, teams are drawn to straight-line speed the most for smaller receivers. The 40-yard dash predicts draft capital with an r-squared of .165 among that group, compared to just .109 among taller WRs.

But raw 40-yard dash time was only slightly more predictive of actual production among shorter WRs (.050) than taller ones (.044), and it becomes even less important when using (weight-adjusted) speed score for shorter receivers (.049) than for taller ones (.059).

With this knowledge, we can more easily predict potential busts by focusing on smaller receivers who improve their draft stock by running well in the 40-yard dash. John Ross, Anthony Schwartz, Parris Campbell, Rondale Moore, Velus Jones Jr., and Andy Isabella are only a handful of many recent examples of this archetype who rose up to Day 2 or earlier.

Only three qualifying TEs above 265 pounds within my database have produced over 500 receiving yards in any single season: Alge Crumpler, Scott Chandler, and Vance McDonald.

Though interestingly, the weight-adjusted 3-cone has mostly identified “smaller hits” in later rounds. Excluding players drafted in Round 1, it’s spotted guys like Dennis Pitta (98th percentile, Round 4), Mike Gesicki (97th, Round 2), and Jordan Cameron (97th, Round 4), with Jimmy Graham (95th, Round 3) by far its biggest success story.

Or at least, overrated for fantasy football purposes. As I explain in the Index, my model targets production within the first three years of a player’s career — since that’s the most relevant window for a player’s dynasty value. But this choice likely juices the observed importance of the 40-yard dash in particular, since that’s the event teams seem to most care about, a factor at its most relevant early in a player’s career with respect to the opportunities they get. Speed demons like Kyle Pitts (99.7th-percentile speed score) and O.J. Howard (97th percentile) were at their most productive early on in their careers, while some of the broad jump’s best performers like David Njoku (99th percentile) and Jonnu Smith (95th percentile) were relatively later breakouts.

Interestingly, both the vertical and broad jump are incredibly strong predictors of which heavy TEs (above 265 pounds) will be drafted highly by teams, sporting r-squared values of .264 and .304, respectively, to draft capital. This is largely irrelevant for fantasy analysis (no TE over 265 pounds in my database has exceeded 120 fantasy points or ~7 FPG within their first three seasons), but I’d hypothesize it’s created a predictiveness illusion that’s been incorrectly applied to more traditionally sized receiving TEs.

Among 302 TEs with below a 75th-percentile SPORQ score, only Jordan Reed, Mark Andrews, Brandon Pettigrew, Chris Cooley, Randy McMichael, and Jake Ferguson bested 175 PPR points (roughly the cutoff for a top-6 season) within their first three years. Andrews and Reed are all-time receiving outliers, Cooley was the most recent fantasy-relevant H-back (over a decade ago), and Ferguson was the 3rd consecutive Day 3/UDFA TE that Dak Prescott managed to make fantasy-relevant (after Dalton Schultz and Blake Jarwin).

There are far too many hits within the 90th percentile to list all of them here (you can check them out on our dedicated SPORQ page), but some of the bigger recent ones include: Rob Gronkowski (91st percentile), Jimmy Graham (98th), George Kittle (100th), Sam LaPorta (92nd), Travis Kelce (92nd), and — if we want to call him one after his 2024 season — Jonnu Smith (92nd). Luke Musgrave (94th) and O.J. Howard (97th) currently look like two of the worst highly-drafted misses.

Ertz has never been athletic but is a route-running and separation savant, even in the twilight of his career. He’s ranked top-3 among TEs and top-40 among WRs in Fantasy Points Data’s Average Separation Score during each of his last two qualifying seasons.

Some of the biggest risers from the weight-adjusted 3-cone include Greg Jennings and Odell Beckham Jr.