This article is long – honestly, it’s more of a “book” than an “article” – but it’s also everything you need to know in order to be a profitable best ball player.

The average player should expect to win 1 out of every 12 (8.3%) of the 12-man best ball leagues they enter. And to beat the rake you’ll have to win about 1 out of every 10 (10.0%) 12-man leagues you enter. If you’ve read this article in its entirety, I’m confident you’ll be positioned for that to be your minimum expectation. And if drafting using our best ball rankings, I don’t see why that figure can’t be much higher, with big profits for those of you who have become as addicted as I am and enter as many leagues as I do.

Note: Special thanks to Mike Beers (@beerswater) for all his help with this article. It would have been impossible without him.

TLDR: TLDRs in bold.

What is a best ball league?

Simply put, best ball is a fantasy format without any in-season management or any time demands beyond the actual draft itself. You just draft your team and then forget about it – or at least until Week 17 when it’s time to collect your winnings.

Best ball is the most low-maintenance fantasy format imaginable. It’s like a mock draft where you can win money. Or, it’s like your typical friends and family league, but without all the tedious stuff – no start/sit decisions, no waiver wire, no add/drops, and no trades.

And while your home league might not draft until late August, best ball drafts operate year-round, pausing only during the actual season. This helps to keep you plugged in and sharp all throughout the offseason, giving you a sizable edge on the opponents in your home league who tend to hibernate throughout most of the offseason. In addition to all this, best ball is also massively fun and addicting – drafting 100-plus teams by the end of an offseason is fairly common.

In a best-ball league, you have the option of playing in a fast draft (30-second pick clock) or slow draft (anywhere from a 4- to 8-hour pick clock). The latter drafts typically take several days or up to a week to complete. One of the benefits of these leagues is that there are no frustrating start/sit decisions to make during the season – your highest-scoring players at each position are automatically slotted into your starting lineup each week. There aren’t any time-consuming add/drops, waiver claims, or trades. For those of you who want to be in more leagues but already have too many rosters to manage, best ball is absolutely perfect.

And there’s no such thing as bad matchup luck, because there are no matchups – final season standings are determined by total points scored across the first 17 weeks of the season. (Remember, the NFL is likely shifting to an 18-week / 17-game schedule this year.)

Best ball is the most exploitable fantasy format, which is to say it’s the easiest to profit from. As I’ll show later on, at least a third of your opponents are making mistakes akin to drafting a QB in Round 1 and a DEF in Round 9. Merely avoiding those mistakes, let alone drafting optimally, can yield a consistently high positive ROI year over year. Some of the best best ball players (the legendary Aaron H, for instance) have never posted an ROI below 50% in seven years of play.

Where can I draft a best ball team?

This season, you can draft a best ball team on DraftKings, FanDuel, Yahoo!, FFPC, Underdog, Fantrax, RealTimeSports, NFFC, or FanBall. (Note: some of these sites aren’t yet live for the 2021 season as of early March.)

Across all of these sites (or, in some cases, apps) and all of their various offerings you can play in a best ball league with anywhere between three and 12 teams drafting. These drafts can last anywhere between 10 to 28 rounds. A league can be PPR, half-point PPR, TE Premium, or something else. Some leagues will be Superflex, most will not. Some leagues will have kickers and defense, most will not. In some leagues you can start up to 4 wide receivers in any given week, and in other leagues as few as 2. Some leagues offer 2 flex spots, some offer zero. Payout structure can vary as well – some leagues will be winner-take-all; others can be as flat as a DFS double-up with the top 50% of teams all doubling their buy-in. Another popular format is a tournament-style league, like the DraftKings Best Ball Millionaire, which awards $1 million to 1st place.

All of these different formats impact the recommended strategy, so we’ll just focus on one format today and then try to hit on the bulk of the others at a later date and in a follow-up article.

FanBall’s BestBall10s, specifically the Classic BestBall10s – formerly known as MFL10s – have been around the longest and, as such, yield the largest sample size of data (28,000-plus drafts since 2015). For that reason, they’ll serve as our best example and the focus for today’s article.

BestBall10s (Classic)

Pricing varies for Classic BestBall10s – between $5-$100 – but the payout structure does not. 1st place gets 10X of their buy-in in winnings, while 2nd place gets half of their buy-in back. The most popular structure offers a $10 buy-in, paying out $100 to 1st place and $5 to 2nd.

BestBall10 scoring is fairly standard: 1.0 point per reception (PPR) and -2.0 points per turnover would be the only things not perfectly uniform across all best ball platforms. Their fantasy season spans the first 17 weeks of the season, and the highest-scoring team over that span wins.

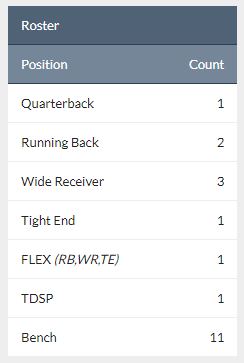

Each draft lasts 20 rounds. Each week your team will be starting 1 QB, 2 RBs, 3 WRs, 1 TE, 1 Flex (RB/WR/TE), and 1 Team DEF, which leaves 11 players left to sit on your bench.

You can draft as many players from as many or as few teams or positions as you want. But you’d be much better off drafting a specific number of players at each position. And certain positions much earlier than others. More on this later.

Key Strategy Differences (Best Ball vs. Start/Sit)

On paper, best ball might not seem so different from a traditional start/sit league. But in actuality, and from a strategy perspective, it’s an entirely different game.

Here are the 3 biggest differences:

1) Certain players become more valuable in best ball.

1A) In a typical start/sit league, a high weekly ceiling does not matter nearly as much as predictability or week-to-week consistency (which we use as a proxy for predictability). In a best ball league, week-to-week consistency doesn’t matter nearly as much as a high weekly ceiling.

In other words, highly-volatile “boom-or-bust”-type players gain value in best ball.

Consider T.Y. Hilton. His best ball win percentage was below average in 2020, but not dramatically so (6.8%). In fact, it was higher than Jarvis Landry’s (6.4%) despite Landry outscoring him (by 21.5 fantasy points) and at a cheaper ADP (a full round cheaper no less). But in start/sit leagues, Hilton’s win% was easily among the worst at the position. Here’s why:

According to ESPN, when Hilton was started in over 50% of leagues, he averaged just 6.1 FPG. And among his nine most-started weeks, Hilton averaged just 5.9 FPG with a high of only 9.9 fantasy points. But across his six least-started weeks, he hit highs of 23.1, 21.0, and 16.1. Basically, Hilton was highly volatile and nearly impossible to predict week-to-week. So, in a start/sit league, Hilton was only ever returning negative value to your team – when you played him, he killed you, and when you sat him, he went off. It’s not hard to see why predictability and week-to-week consistency are so important in start/sit leagues. But in a best ball league, you got all of Hilton’s boom games without having to suffer the consequences of his dud games. When he went off, he automatically slid into your starting lineup. When he didn’t, he stayed on your bench.

Let’s also consider Larry Fitzgerald and Allen Lazard. Even though Fitzgerald outscored Lazard by the season’s end, and with a cheaper ADP no less, Lazard still finished the season with a higher Win% in best ball. Despite outscoring Lazard, Fitzgerald’s weekly ceiling was so low that it was possible he never once cracked your starting lineup. Fitzgerald posted a season-high of just 14.2 fantasy points, but Lazard trumped that twice, and dramatically so, with outputs of 26.4 and 18.2 fantasy points. While 26.4 fantasy points from a WR (unscientifically) makes it into your starting lineup 99% of the time, that number might drop to 50% with a 14.2-fantasy-point performance. And even if it did crack your starting lineup, it’s not returning as much value over the next highest-scoring WR (the one on your bench) as a 26.4- or 18.2-point performance. Clearly, week-to-week upside is extremely valuable in best ball.

Hopefully these examples got the point across, but our best examples will come from the running back position. More on this later.

Sidebar: My preferred method of measuring consistency and volatility is by coefficient of variation. At a later date, I’ll be publishing articles looking at the most- and least-consistent players by usage and production. See prior-season examples here (for production) and here (for usage) as an example.

1B) While week-to-week upside certainly matters more in best ball, full-season upside matters less, and safety matters more.

In fantasy football, a player’s upside is far more valuable than their downside is detrimental. In a start/sit league, so much of winning your league comes down to just nailing the right 1-3 players, even if you get the other 60% of your draft wrong. In other words, “Upside Wins Championships.”

But that’s far less true in best ball, where you don’t have the safety net of a free agency pool. The top-end league-winners at the highest end of the Pareto distribution – players like Alvin Kamara and Travis Kelce in 2020 – are still extremely valuable in best ball, but they lose some of their potency in comparison to start/sit leagues. In best ball, merely drafting a high percentage of slight ADP-beaters can be just as effective as the teams who nailed Justin Jefferson, Robby Anderson, and Brandon Aiyuk in the later rounds but weren’t as consistent with their other picks.

Consider Mecole Hardman and Cole Beasley. Hardman was going a full 10 rounds earlier in drafts last year (Round 8 vs. Round 18), and, while that might have made sense in a start/sit draft it made little sense in best ball. Hardman’s range of outcomes were viewed something like this by start/sit drafters: 20% chance he’s an every-week must-start WR1 or WR2, 80% chance he’s who he was in 2019. For Beasley, it was something like: 80% chance he beats his lowly ADP but is still unlikely to be an every-week starter and a top-40 option, 10% chance he’s worthless, 10% chance he’s a near-every-week starter and a top-36 option (this happened, but that’s not the point right now).

Players like Hardman make a lot more sense in start/sit, but players of the Beasley archetype are far more valuable in best ball. I explain this – and the Upside Wins Championships draft philosophy – all in more detail here. Seeing as how Hardman and Beasley had the same ADP differential in best ball and start/sit, it’s clear your opponents aren’t thinking like this. And, thus, that’s another edge to us.

Sidebar: This distinction is true for 99% of all best ball drafts, but not as much in a DraftKings-style tournament where upside is everything and you need to finish in the top 0.01% of teams.

And, to be fair, maybe this wasn’t the perfect example, because Hardman was also viewed as a high weekly-ceiling type player, while Beasley was not. So, note, there’s a gray area here. Lazard was more valuable than Fitzgerald (due to a higher weekly ceiling), but Beasley was more valuable than Hardman (more total points scored).

2) Just like how some players will be worth a lot more in best ball, certain positions are going to be worth more as well. For instance, QBs and WRs are worth a great deal more in best ball than in typical start/sit leagues. High-end TEs are also more valuable in best ball. But high-end RBs (but not the highest end RBs) are going to be worth a lot less in best ball. And the Zero-RB approach, though deleterious in start/sit, is far more effective and very much viable in best ball. I’ll explain further and in more detail in our next section.

3) Drafting the right number of players at each position is crucial to your success, in many cases just as much if not more than drafting the right players. For instance, on FFPC, teams that drafted exactly 3 Kickers and 3 Defenses won 10.2% of the time. Teams that drafted just 2 of each won only 7.2% of the time. Teams that drafted 4 of each won 8.3% of the time. Remember, your expectation going in was just 1-out-of-12 (8.3%), and a 1-out-of-10 win-rate (10.0%) is typically more than enough to beat the rake and generate a profit. Simple changes like this can yield a tremendous edge. Of course, it’s also important we’re drafting the right positions in the right rounds. You shouldn’t be drafting kickers and defenses in single-digit rounds. But I’ll dive in deeper into this in our next section.

Roster Construction (General)

There’s no ideal best ball strategy, nor a truly optimal roster construction. Everything is unique to your specific league type, your specific draft, and the specific season in which you’re drafting. Is it optimal to draft exactly 3 QBs? It depends. Is this a superflex league? And who were the first 2 QBs you drafted? Where did you draft them? Who is still on the board? What does the rest of your team look like?

But with all of this being said, paying close attention to historical win rates – which you can find for FanBall here and FFPC here – can go a long way in maximizing an edge over your opponents.

Sticking with Classic BestBall10s as our focus, here’s what has been the most successful roster construction since 2015:

Quarterback: 2-3 (Optimal: 2)

Running Back: 5-6 (Optimal: 5)

Wide Receiver: 7-8 (Optimal: 8)

Tight End: 2-3 (Optimal: 2)

Defense: 2-3 (Optimal: 3)

The above approach yields an expected win-rate of at least 9.5% for any possible combination above. And the highlighted optimal sits at 10.5%.

Keep in mind, included within this sample are foolish teams that, though they drafted only 3 defenses, might have drafted all 3 defenses in the single-digit rounds. Just as it’s important to draft the right number of positions, it’s also important to draft the right positions in the right rounds. And if optimizing for round selected, we can actually see our win-rate jump above 16% in some instances. That’s a massive edge. Think about it; just knowing which positions to draft and when, as opposed to which players – so, basically, just drafting off of ADP – can double our chances of winning a league, essentially knocking 5 or 6 of your opponents out right off the bat (odds increasing from 1-out-of-12 to 1-out-of-6). It’s like entering a beer pong game with your opponent already down 3 cups. It’s something easy to do that requires no skill or effort whatsoever, but it materially increases your odds of winning.

The “optimal roster construction” outlined above is only optimal in a vacuum. But drafts don’t exist in a vacuum. The above approach seems optimal, but what happens if you drafted WRs with all 5 of your first 5 picks? Is 8 WRs still optimal, or should you now go with 7 to provide extra support for your now ailing RB position?

This sort of thinking led Mike Beers of RotoViz – the industry’s preeminent best ball expert – to coin the term “conditional roster optimization.” He explains all of this in his own words in a terrific Twitter thread here. I’ll go ahead and give you the (paraphrased) summary, but I highly encourage you to read it in full.

So, what happens if you draft 5 WRs with your first 5 picks? Would that mean 8 WRs total is no longer the optimal number of WRs to draft? Beers responds, “The answer, of course, is that the optimal construction does change based on the picks you make early in the draft. I often think of it as one of those balance scales – a RB drafted in the 2nd round clearly should not be equivalent to a RB drafted in the 12th round.” But does a RB drafted in the 5th round plus a RB drafted in the 8th round equal a RB drafted in the 2nd round? Maybe. Good question – that’s at least the right way to think about this.

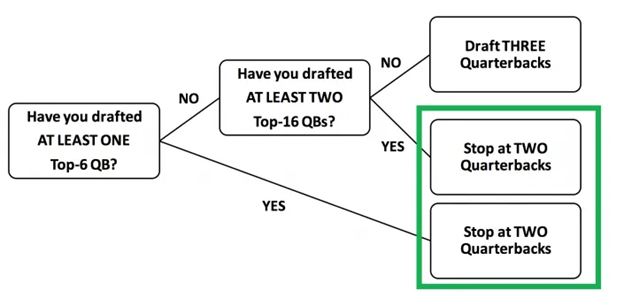

He continues, “It became clear to me that where you picked your players (how much ‘draft capital’ you spent on positions) impacted how many you should be drafting. Here's a pretty straightforward decision tree that came out of this:”

A roster needs to have balance, and one must understand the tradeoffs one is making each time they pick one position over another. “The whole thing is a balancing act between quality and quantity.” Drafting 2 TEs in the first 5 rounds means you don’t need a 3rd, because you’re stacked at TE and can only start a maximum of 2 each week, and you’re also now weaker than every other team at the other positions. Conversely, punting TE until the double-digit rounds means you now have to make up for your lack of quality at the position with a quantity approach (by drafting 3).

Most best ball experts and pros I’ve talked to say they don’t start thinking about roster construction until after the first 5 or 6 rounds of the draft. Early on, they’ll just let the draft fall to them, and try to scoop up value where they can. But after that, roster construction surely matters a great deal, and so they’ll start looking at where they’re weak and where they’re strong. Already have 4 WRs? Okay, you can neglect the position for a while, and worry more about strengthening your RBs. Beers echoes that sentiment here, saying:

“The number one thing about a best ball draft strategy, to me, is that you should not go in with ‘a’ plan… you should go in with 20+ plans. At least 5 of them are eliminated with each pick that you make and as the balance of the roster takes shape. The real plan is flexibility, and balance. By keeping your roster balanced across positions, through quality, quantity, or a combination thereof, you put yourself ahead of the field. And then if you're really good at picking individual players, your opponents don't stand a chance and even if you AREN'T really good at picking players, you DO stand a chance. In many cases the edges from optimized roster construction are small, sure. But what a lot of people miss is that there are dozens of these edges, and they ADD UP.”

Okay, with all of this in mind, what is the “optimal” strategy at each position?

Note: Remember, we’re only looking at FanBall’s BestBall10s, though a lot of what we’re going to be talking about is universal across all best ball formats.

Quarterbacks

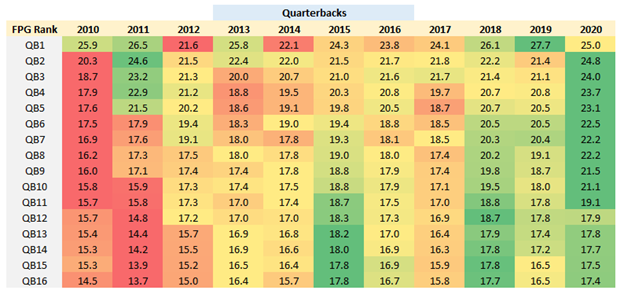

“Late round QB” has long been the recommended approach in 1QB start/sit leagues. And not without good reason – the results simply speak for itself. But a late-round approach at QB wouldn’t get you very far in best ball.

For one thing, QBs are far scarcer in best ball. In a typical 12-team 1QB start/sit league, we shouldn’t expect more than 16 QBs to be drafted or rostered at any given time, and, at most, 24 QBs. However, on average, we should expect 29.6 QBs to be drafted in any given BestBall10. Keep in mind, there were only 25 QBs to start in over 10 games last year. And today, how many QBs can we project with any level of confidence to start Week 1? And then, of those, how many might have a high risk of getting benched should they struggle after the first few weeks of the season? Or, what are the odds that that team surprises us and drafts a QB in the first round?

Related to this point – without the benefit of a waiver wire or the ability to stream, QBs gain more value. Using only QBs rostered in fewer than 50% of leagues each week, Sean Koerner streamed his way to QB6- and QB11-levels of production the past two seasons. In a low-scarcity league with add/drops, this crushes the draft value of all QBs.

Similarly, Justin Herbert was rostered on only 1.7% of teams in Week 2 and 11.8% of teams in Week 4. By Week 11, 93%. He posted the 2nd-highest win-rate at the position in BestBall10s last year, but was drafted in fewer than 1 out of every 10 leagues. In a 1QB start/sit league, it always makes sense to wait at the QB position. Because even if you don’t draft a single QB, you still have a floor of about QB6-QB11 levels of production just on streaming alone. And, if you’re lucky, something better than that if you managed to scoop up a 2020 Justin Herbert, 2019 Ryan Tannehill, or 2018 Patrick Mahomes off of waivers.

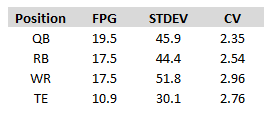

Another, more minor point – QBs have the highest FPG average and a fairly high standard of deviation to their week-to-week production. So, that could also play a role here – remember, a high weekly ceiling and increased volatility are seen as positives in best ball. Here’s how the top-20 players ateach position fared over the last three seasons:

QBs are far more valuable in best ball than start/sit. That’s pretty true across the board, regardless of your preferred best ball provider. But let’s look at FanBall’s BestBall10’s specifically.

More or less, the optimal approach is something that looks like this:

QB1: R7-11 (Optimal: R7-8)

QB2: R9-12 (Optimal: R10-11)

QB3 (Optional): R11-13 (Optimal: R13)

You don’t want to be the 1st or 2nd person to draft a QB, and you don’t really want to draft a QB before Round 5 – historical win-rates say that’s a bad idea, likely due to the fact that the QB position sports an extremely poor correlation between ADP and fantasy production.

And you also don’t want to wait too long on drafting a QB. Otherwise you’re stuck with the Mitch Trubiskys and Ryan Fitzpatricks of the world. How confident are we that these QBs will start in Week 1 or for the majority of the season? Not very.

As we discussed earlier, you should only ever be drafting 2 or 3 QBs. A good rule of thumb is something like this: If you’ve already drafted 2 QBs before Round 12, stop there. If you haven’t, consider 3 if and only if you can land one likely to be a full-season starter.

Here are some of your different options and the realistic returns from each approach:

2QBs – early QB1 / mid-range QB2 – 9.0% win-rate

2QBs – mid-range QB1 / mid-range QB2 – 9.9% win-rate

3QBs – 3 mid-range QBs – 10.3% win-rate

3QBs – early QB1 / mid-range QB2 / mid-range QB3 – 10.0% win-rate

3QBs – early QB1 / mid-range QB2 / late QB3 – 8.7% win-rate

But again, remember that every season is unique. We’re coming off the worst year maybe ever for Late-Round QB. And this offseason presents us with more uncertainty than I remember seeing in a number of years. So maybe it’s worth bumping up QB even more this year than these numbers might imply.

Running Backs

Just like how “late round QB” loses efficacy in best ball, “Bell Cow or Bust” also loses its appeal in best ball. Conversely, “Zero-RB” becomes a far more viable strategy. Why? Because high-end RBs (but not the highest end RBs) are simply less valuable in best ball. I explained this in more detail here, but let’s use a more current example to illustrate the point.

Consider Aaron Jones, Nyheim Hines, and J.D. McKissic. Jones was one of the most valuable players in fantasy last year. If you rostered him in a 10-team ESPN league, your odds were better than a coinflip to make the playoffs. The odds for Hines and McKissic were only marginally better than average. According to fantasy WAR, Jones was over 3X as valuable as either player. For one thing, Jones greatly outscored both Hines and McKissic – Jones ranked 4th among all RBs in FPG, while Hines and McKissic ranked (respectively) 26th and 25th. For another, Jones was an easy every-week must-start, while Hines and McKissic were far less predictable. For instance, Hines – who was never started more than 47% of the time in any given week – averaged 16.4 FPG across his five least-started games, and just 7.1 FPG across all other games he played. But, of course, that doesn’t matter at all in best ball. That’s one reason Hines and McKissic were far more valuable relative to Jones in best ball.

Another reason is this: a quantity over quality approach is very much viable in best ball, while such a strategy is not at all viable in start/sit. (You can’t stream the RB position like you can with QBs.) Jones greatly outscored Hines and McKissic last season, who were both far more volatile and far less predictable. But, if in a best ball format (taking the higher score in each week), and if treated as one player, Hines and McKissic were worth a combined 275 fantasy points (ignoring production that might have come in the flex). This would have ranked ahead of all RBs not-named Alvin Kamara, Dalvin Cook, and Derrick Henry, and 16 points above Jones. Keep in mind those 3 RBs and Jones were all being drafted in the first 2 rounds, while Hines and McKissic were both being drafted outside of the top-50 RBs.

Unsurprisingly, Hines’ Win% jumped by 40% moving from start/sit to best ball, and McKissic’s jumped a whopping 90%. Both RBs were merely worthy of rostering in start/sit, but they were borderline league-winners in best ball. Clearly, a “wait at RB” approach is very much viable in best ball. Well, with one exception…

You should still be drafting a RB with your first (ideally) or second pick. That’s proven to be the optimal strategy in almost every instance. But after that, you can actually afford to wait quite a bit at the position, and quite a bit longer than basically all of your opponents seem to realize.

If you’ve drafted a RB in Round 1 (ideally) or Round 2, you’re better off waiting until at least Round 6 before drafting a second RB. In BestBall10s, teams that drafted their RB1 before Round 3 and their RB2 after Round 5 won 10.6% of the time (and 11.1% if ending up with 5-6 total RBs). Teams that drafted their RB1 before Round 3 and their RB2 before Round 5 won only 8.1% of the time.

Although the numbers strongly suggest you’re better off waiting to draft your RB2 and RB3, a whopping 64% of teams draft a RB2 before Round 5, and 69% of all teams draft 3 RBs before Round 8. In other words, it appears a lot of your opponents are drafting suboptimally, representing a sizable edge to you.

Here’s what the optimal approach looks like in BestBall10s:

RB1: R1-2 (Optimal: R1)

RB2: R6-10 (Optimal: R8-10)

RB3: R9-13 (Optimal: R12-13)

RB4: R13-17 (Optimal: R15-16)

RB5: R14-20 (Optimal: R17-18)

RB6 (Optional): R16-20 (Optimal: R19-20)

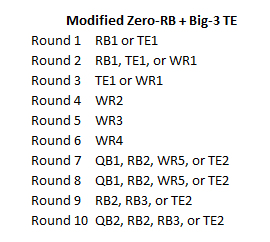

Drafting a RB in one of the first 2 rounds and then neglecting the position for multiple rounds (as the optimal approach outlined above suggests you do) is called “the modified Zero-RB” strategy. This strategy does have one of the higher historical win-rates (11.1% to 11.9% for the approach shown above) ignoring everything else you might do at the other positions. (The difference in win-rate between 5 or 6 total RBs if following this approach is negligible, so make that decision based on which RBs are available later in your draft.)

But what happens if you miss out on a RB in the 1st 2 rounds? Well, that’s not very good. Teams that failed to draft a RB in the 1st 2 rounds won only 7.7% of the time. You could try to do something like grab 3 RBs across Rounds 3-7, but the data suggests you should go full-on Zero-RB. And know that if you do, you should be drafting 6 or 7 total RBs, as opposed to just 5.

Disclaimer: The modified Zero-RB approach is slightly less effective in FFPC, where you can start the same number of RBs and WRs each week.

Wide Receiver

Okay, so if Zero-RB is a far more viable strategy in best ball, the next logical assumption is that WRs are also more valuable in best ball. That’s exactly correct! And especially so in BestBall10s, where you’re forced to start between 3 and 4 WRs each week – as opposed to FFPC which requires you to start between 2 and 4 WRs each week (same as RBs). You’d think that because there are so many more fantasy-viable options at the WR position (in comparison to QBs, RBs, and TEs), you can get away with more of a quantity over quality approach, but the numbers don’t bear that out.

In BestBall10s, you should go out of your way to draft between 4 and 5 WRs before Round 9. Drafting 4 WRs before Round 8 yields a win-rate of 9.8% if drafting 7 WRs total. If waiting until after Round 8, your win-rate drops to 8.1% (if ending with 7) or 8.5% (if ending with 8). And drafting 5 WRs before Round 9 yields a win-rate of 10.1%. But the WR-heavy approach posts diminishing returns beyond that. After drafting your 4th or 5th WR in the single-digit rounds, you’re better off waiting until at least Round 13.

The optimal strategy in BestBall10s is either modified Zero-RB, grabbing a Big-3 TE, or a combination of the two. If going the modified Zero-RB route you need to draft a RB in Round 1 (ideally) or Round 2 (odds are still good, but not as optimal), and then draft 4 WRs before Round 8. This strategy typically yields around a 10.3% win-rate. You can also draft a 5th WR before Round 9 if you find the right guy, as this approach yields a 10.1% win-rate. In either case there’s diminishing returns beyond that. You should only end up with 7 WRs total, and, more importantly, you should wait on drafting your next WR until after Round 12. In doing so you’ll see your win-rate jump to 11.3%.

Again, the high-end RB1s are going to be the biggest league-winners. They’re the highest scorers, they have the highest floor, they have the highest ceiling, and they offer the most relative value over their in-position peers. You don’t want to pass up on one of these “uber-backs.” But otherwise, yes, after the high-end RB1s, the WR position is much more valuable than RB in best ball.

For one thing, WRs offer a higher weekly ceiling. Last year, there were 41 instances of a WR eclipsing 30 fantasy points in a game. But there were only 25 such instances among the RBs, and 10 of those (40%) came from the top-3 RBs.

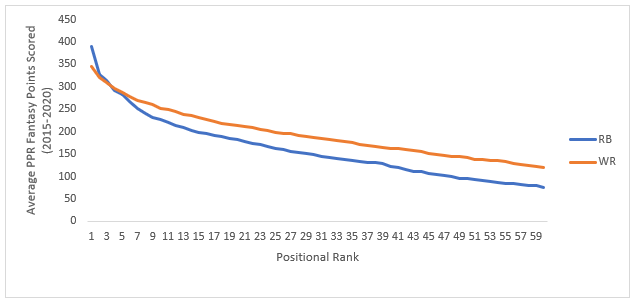

More importantly, and more simply, after the highest tier of RBs, WRs simply outscore RBs.

WRs out-score RBs, which is an important factor on its own, but is especially important in leagues with a flex spot – WRs are going to crack your flex spot far more often than RBs.

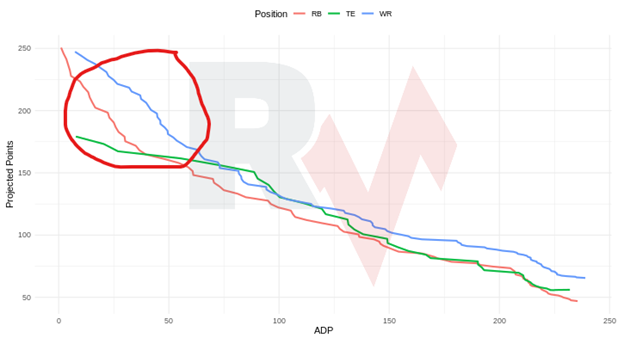

Factor in historical ADP and it’s clear, WR is also where all the value is – WRs are dramatically out-producing RBs drafted at the same ADP, which is to say the bulk of your opponents are overvaluing RBs and drafting suboptimally. Here’s a great chart from RotoViz illustrating this point (this is from their Win the Flex App):

Here’s what the optimal WR construction tends to look like in BestBall10s:

WR1: R1-R4

WR2: R3-R6

WR3: R4-R6

WR4: R5-R7

WR5: R6-R8 or R13-R20

WR6: R14-20

WR7: R15-20

Tight End

TEs, like QBs, are scarcer in best ball. Because they’re scarcer, they’re more valuable.

In a start/sit league, it’s uncommon to ever see more than 16 TEs drafted or rostered at any given time. But in a BestBall10, we’ll typically see 30.9 TEs drafted. And, without the luxury of the waiver wire and the ability to make add/drops, we also lose the ability to stream the position. Or, better yet, pick up someone like a 2019 Darren Waller midseason.

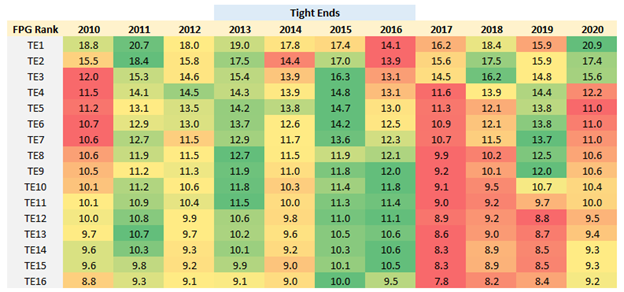

And high-end TEs are far scarcer than high-end QBs. While QB production is fairly flat across the top 50% of the spectrum (at least historically), the TE position is far more top-heavy. (In 2020, the TE1 out-scored the TE10 by 55%. The QB1 out-scored the QB10 by 19%.) So, it shouldn’t be too surprising that high-end TEs become far more valuable than high-end QBs in best ball. While that’s also true in start/sit, an added bonus in drafting a high-end TE in best ball is you don’t need to spend any draft capital on a third TE, allowing you to allocate resources elsewhere. And unlike the QB position, your second TE can also contribute in the flex.

Travis Kelce scored 315 fantasy points in BestBall10s last year. That was almost exactly double the 7th-highest scoring TE over this span. The No. 3, No. 4, and No. 5 highest-scoring TEs combined to score 532 fantasy points. But, if in a best ball format (taking the higher score in each week), and if treated as one player, they combined to score just 259 fantasy points. Of course, we're neglecting any points one of these TEs might have scored in the flex. But still, this is absurd. At the TE spot, Kelce alone (bye week factored) was 22% more valuable than the No. 3, No. 4, and No. 5 highest-scoring TE combined. Factor in draft capital – one Round 2 pick vs. 3 mid- to later-round picks – and it’s clear, Kelce was a massive cheat code in best ball.

In case you’re wondering, in 2021, Kelce is an easy Round 1 pick. In fact, he should probably be selected in the mid-1st in BestBall10s, ahead of any other non-RB. Darren Waller and George Kittle are also worthy early round picks. But then the tier dies.

If you manage to grab one of the Big-3 TEs, you’re sitting pretty. Historically, drafting your TE1 before Round 5, and ending the draft with only 2 TEs yields an 11.1% win-rate – rivaling modified Zero-RB as the best possible strategy. If you draft your TE1 after Round 4, your win-rate drops to either 7.6% (if you finish with 2 total TEs), 8.0% (if you end up with 3), or 6.0% (if you end up with 4).

The best way to improve those odds – if you do miss out on one of the Big-3 TEs – is to draft 3 mid-to-late round TEs (9.4%). But just don’t wait too late.

Drafting RBs and WRs in the later rounds is a great idea, but not so much with QBs and TEs. The well dries up too fast. On average we should see 31 TEs drafted in any given BestBall10, but last year only 21 TEs hit triple-digits in fantasy points, while 75 WRs hit the same mark. Believe it or not, simply neglecting QBs and TEs in the later rounds can yield a sizeable edge. Just never drafting a QB or TE after Round 14 improves your win rate to about 9.6% in BestBall10s.

But, yeah, more or less the optimal approach looks something like this:

Option 1 (~11.5%): Draft TE1 before R4 or R5. Draft TE2 before Round 13. Don’t draft another TE.

Option 2 (~9.4%): Draft TE1 and TE2 between Rounds 8-11. Draft TE3 before R14. Don’t draft another TE.

Defenses

Don’t worry too much about this.

In BestBall10s, only draft 2 DEF (8.6%) or 3 DEF (9.2%). And don’t draft a DEF before Round 15 (9.4%). Quantity matters more than assumed quality, and it doesn’t really matter too much which DEFs you take. Everyone is bad at drafting defenses.

Other Important Tips

1. Stacking is probably a +EV strategy in best ball, but certainly not as +EV as most people think. In theory, it’s a great way to raise your ceiling without taking on too much risk. Remember, you’re trying to finish 1st place out of (typically) 12 teams – in a $10 Classic BestBall10, 1st place pays out 20X as much as 2nd place, while 3rd place makes nothing. The idea behind it is if you’ve already invested draft capital in a QB, and since you need that pick to hit, it’s unlikely that QB hits and his receivers struggle. Or vice versa. And if that QB was a miss, your odds already aren’t too good anyway. This would be true across the full season (a QB and his receivers both having a big year) and week-to-week (a QB and his receivers having a big blowup week).

But again, stacking is nowhere near as important as people think. The best stacks are a QB1+WR1+WR2 stack and a QB1+WR1+WR3 stack, but the win-rate on both wasn’t very high (both at 9.3%). And almost all of the other stacks you’d expect to rank highly, barely finished above average if at all. So, realistically, don’t worry too much about stacking. Maybe only go that route if needing to break a tie between two similarly ranked players.

However, stacking is going to be more important in a DraftKings-style tournament best ball league, where you need all the upside you can get to finish in the top 0.01% of teams.

2. On the other hand, handcuffing is a proven -EV strategy, having the opposite effect – you’re sacrificing upside to raise your floor. It’s simply a too costly insurance policy given the payout structure. Mike Beers discussed this in more detail here.

3. The optimal draft strategy when it comes to picking individual players (as opposed to individual positions) is something like what I described here. Use our best ball rankings and site ADP in tandem. If we have a player really high, but he’s a lot lower by ADP, you should draft him later. That way you get more value and give yourself an even bigger edge.

4. If you’re going to be drafting a high number of teams, make sure you’re paying close attention to ADP and are grabbing the big ADP values when they fall. This will help bring down the average cost across all of your drafts, which is highly beneficial to your portfolio of teams.

5. If you’re going to be drafting a high number of teams, it’s important to diversify the players you’re taking, especially early in drafts. The most profitable best ball players I’ve talked to, all say they only take extreme hardline stands in final rounds of their drafts. If those late-round players flop it really doesn’t really hurt you, but that is the optimal time to be drafting for upside and swinging for the fences with your picks – a 17th-Round WR was unlikely to crack your starting lineup more than once or twice anyway. Among players in the single-digit rounds, Best Ball pros are unlikely to ever have less than 5% exposure or more than 25% exposure to any individual player. Here’s a great example why:

Last year, Travis Kelce posted the highest win-rate in BestBall10s. If you drafted him, you won 24.4% of the time. If you drafted Saquon Barkley, you won 0.3% of the time. That’s an unreal difference – Barkley hurt you more than any two players might have helped you. Kelce improved your odds by a magnitude of 3X, Barkley hurt them by a magnitude of 28X.

6. In the later rounds, avoid QB and TE and chase upside – it’s unlikely your WR7 was going to do much for you anyway, so why not grab a guy who (although perhaps unlikely to beat ADP) has high-end potential if everything breaks his way? He could be a league-winner. And make sure you’re considering how the players you’re drafting fit with the other players you’ve already drafted. A blend of boom-or-bust and high-floor options at the WR position is preferable to going all-in on one or the other. When drafting a second TE after Kelce, remember that this player is unlikely to outscore Kelce. He’s really only there for bye weeks, in case of injury, and (most importantly) to occasionally crack the flex spot. So, it makes more sense drafting a boom-or-bust option like Robert Tonyan than a high-floor TE like Hunter Henry.

6. Getting auto-picked a poor player who doesn’t fit your roster construction can crush your odds of winning, so avoid that at all costs. For that reason, when doing multiple drafts simultaneously, I prefer to do the extra-slow (6-hour clock) drafts and set a timer on my phone to go off every 5.5 hours.

7. Your most profitable month is probably going to be August, when all of the fish have come out of hibernation. But February through April won’t be too far behind, and especially not if you’re a fan of college football and know who all the best incoming rookies are. Luckily for you, even if you’re not, Wes Huber’s articles and the Fantasy Points Draft Guide with Greg Cosell's prospect evaluations are here to help.

Drafting the right rookies before the NFL Draft (when they’ll become far more expensive) is a massive edge. Players like Alvin Kamara, James Robinson, Justin Jefferson, Kareem Hunt, Saquon Barkley, Terry McLaurin, Brandon Aiyuk, and many others were all massive league-winners in their rookie seasons. And they provided more value to you earlier on when they were discounted by sometimes 5-10 rounds. I’ve discussed this in more detail here, as has Mike Beers here.

Bonus: Wes Huber thinks Amon-Ra St. Brown is an ideal late-round draft pick in best ball and a borderline Round 1 talent (NFL Draft). And I might like Elijah Moore from a Year 1 perspective even more. Both are currently going undrafted in 90% of all BestBall10 leagues.

8. You typically don’t want to be the first or second person to draft a QB in best ball. The historical win-rate there isn’t very good. You don’t want to draft a QB too early, but if you’re going to, you should do it earlier in the year. High-end QBs are cheap only up until the fish come out and start overdrafting them. I talked about this here, alongside the point that mid-tier RBs are at their riskiest and least-valuable prior to free agency and the NFL Draft.

9. Bye weeks are overrated. You can use byes to break ties, and especially when you’re only drafting two players at a position, but for the most part that’s something the pros rarely pay attention to.

10. After reading all of the previous 7,000 words in this article, you might think that the optimal approach for the first 10 rounds of a BestBall10 would look something like this:

And, well, that’s sort of right. But the best players I talked to don’t think about the game in this way. Instead, they let the draft fall to them for the first 5-6 rounds, and then start worrying about roster construction. I think Mike Beers put it best when he said: “You should not go in with a set plan… you should go in with 20+ plans. At least 5 of them are eliminated with each pick that you make and as the balance of the roster takes shape. The real plan is flexibility, and balance.”