In last year’s Best Ball Primer & Strategy Guide I wrote 7,000 words explaining the best ball format and how to optimally game it so that it was nearly impossible for you not to profit.

That article was more of a general guide, but focused mostly on NFFC’s BestBall10 format, because that format gave us the most robust sample size of data to analyze. Today’s article will be a synopsis of last year’s piece while focusing mostly on Underdog’s various best ball offerings.

Note: Special thanks to Mike Beers (@beerswater) and Chris Wecht (@ChrisWechtFF) for their help with this article. It would have been impossible without them.

What is a best ball league?

Simply put, best ball is a fantasy format without any in-season management or any time demands beyond the actual draft itself. You just draft your team and then forget about it – or at least until Week 17 when it’s time to collect your winnings.

Where can I draft a best ball team?

If you’re going to be joining a best ball league, there is no better place to look than Underdog Fantasy. They have the slickest, cleanest, least-buggy, and the most user-friendly app in the space. Their rake is minimal (<11.5%). And the payouts can be massive (up to $2 million).

And, lucky for you, if you sign up today using promo code FANTASYPTS, Underdog will match your deposit up to $100! Click here for more info.

An overview of Underdog drafts

Underdog has multiple offerings, so you can find whichever format works best for you. You can draft against anywhere between two and 11 other teams. Entry fees range from $3 and $100. First place prizes range from $8 to $2 million. And you have the option of joining either a “fast draft” (pick clock: 30 seconds) or a “slow draft” (pick clock: 8 hours).

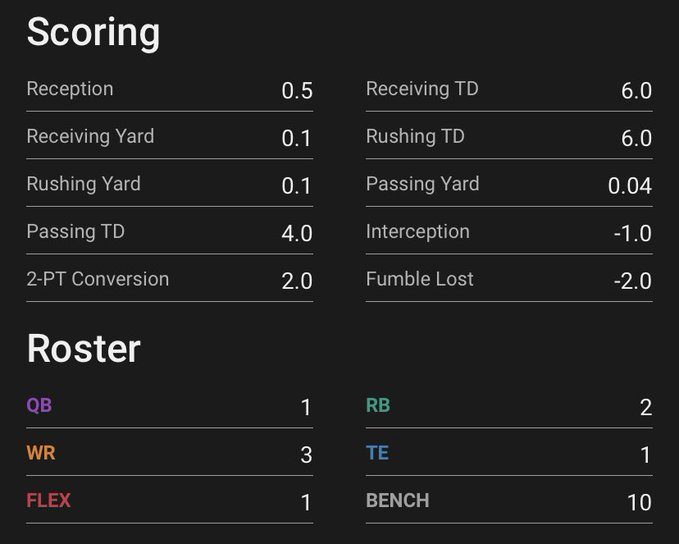

But typically, all leagues are going to be 18 rounds. You’ll start exactly one quarterback, two running backs, three wide receivers, one tight end, and one flex player every week (bench: 10). Scoring is just about uniform to the industry standard, except: 0.5 points per reception, -1.0 point per interception, and -2.0 points per fumble lost.

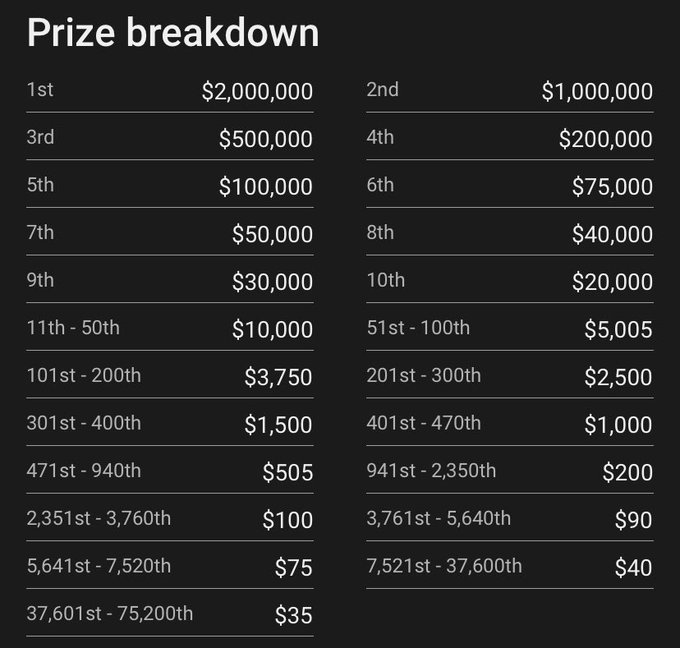

Payout structure varies depending on the league joined. For instance, a $3-entry 12-person draft will pay out $20 to 1st place, $9 to 2nd place, and $3 to 3rd place. But Underdog’s Best Ball Mania III ($25 entry fee) is a progressive elimination contest that pays out $2 million to 1st place, $1 million to 2nd place, $500,000 to 3rd place, and so on until you get to the team finishing 37,600th, which gets $40.

Notes: Along with all this, the top scorer of the Best Ball Mania III regular season (Weeks 1-14) will be awarded $1 million.

Underdog’s standard 3- to 12-person drafts are not too dissimilar to FanBall’s BestBall10s. If you’re looking solely to make a profit, or merely looking to scratch your mock draft-itch and have some money at stake, these are the drafts for you. If all you did was read last year’s Best Ball Primer & Strategy Guide and periodically referred to our best ball rankings, I’m confident you’ll be able to break even at an absolute minimum.

Think of Underdog’s traditional 12-person draft the same way you would DFS cash games; they’re safer and easier to win. Think of their tournament-style leagues the same way you would a DFS tournament (GPP) — they’re more fun, and if you do win, you stand to win a lot more money.

Underdog currently offers two different tournament-style contests: “The Puppy” and “Best Ball Mania III.” (Though they may add more later in the season.)

The differences between these two contests are entry fee ($5 vs. $25), rake (10.5% vs. 11.3%), field size (111,780 max entries vs. 451,200), and payout ($75,000 to 1st place vs. $2 million).

Both contests operate in roughly the same way, but for clarity, in Best Ball Mania III:

Regular Season: The top-2 highest-scoring teams in each league (16.7% of all entries) from Weeks 1-14 will advance to the next round of play.

Quarterfinals: Round 2 then consists of 7,520 10-person leagues, and each league’s highest-scorer in Week 15 advances to the next round (1.7% of all entries).

Semifinals: Round 3 consists of 470 16-person leagues, and each league’s highest-scorer in Week 16 advances to the next round (0.1% of all entries).

Finals: The remaining 470 entries will all battle it out in the final round for 1st place. The highest-scoring team in Week 17 gets $2 million. The lowest-scoring team (470th place) gets $1,000.

Key Differences (Best Ball vs. Redraft)

1) Certain players are more valuable in best ball. In a typical start/sit league, a high weekly ceiling does not matter nearly as much as predictability or week-to-week consistency (which we use as a proxy for predictability). In a best ball league, week-to-week consistency does not matter nearly as much as a high weekly ceiling.

2) Just like how some players will be worth a lot more in best ball, certain positions are going to be worth more as well. For instance, QBs and WRs are worth a great deal more in best ball than in typical start/sit leagues. High-end TEs are also more valuable in best ball. But high-end RBs (but not the highest-end RBs) are going to be worth a lot less in best ball. And the Zero-RB approach, though deleterious in start/sit, is far more effective and very much viable in best ball.

3) In best ball, drafting the right number of players at each position is crucial to your success, in many cases just as much if not more than drafting the right players… Of course, it’s also important we’re drafting the right positions in the right rounds.

Key Strategy Differences (Traditional Best Ball vs. Best Ball Tournament)

In a traditional best ball league – where you don’t have the safety net of the free agency pool to fall back on and you’re competing against only 11 other teams – you want to be a little more risk-averse, you want to prioritize high-floor players a bit more, and you really need to have a balanced roster. But in a best ball tournament…

As we explained earlier, you’re going to want to treat a best ball tournament-style league the same way you would an extremely top-heavy GPP in DFS. Think of Underdog’s Best Ball Mania III the same way you would DraftKings’ Millionaire Maker or FanDuel’s Sunday Million. To that point, upside is everything. After all, you are hoping to finish 1st out of 451,200 teams – a 0.0002% outcome – rather than 1st out of 12 teams (8.3%). And 1st place should be what you’re aiming at; the payout structure in Best Ball Mania is very top-heavy – 1st place gets $2 million, 11th place gets only 0.5% of that ($10,000).

Last offseason, I wrote nearly 5,000 words on the importance of upside in fantasy football. To summarize:

“Leagues are won and lost, not by balanced teams drafting a number of good-to-great ADP-beaters, but by teams who correctly identified a few key league-winners and rode those players all the way to a Championship title.”

For instance, last year, it was nearly impossible to make the Best Ball Mania finals without at least one of Mark Andrews or Cooper Kupp. Andrews was on 66% of all finals teams, Kupp was on 46%, and no other player eclipsed 29%. And then, it was nearly impossible to finish 1st in the finals without Ja’Marr Chase, who scored 50.1 fantasy points in Week 17 (60% more than any other WR).

“In fantasy football, two nickels are never worth a dime. And a few strikeouts here and there are always more than negated by a homerun elsewhere in the draft.”

For instance, many of the top teams last year had several players who never once cracked their starting lineups – fantasy busts like D.J. Chark, John Brown, Henry Ruggs, K.J. Hamler, Dyami Brown, James White, Parris Campbell, Phillip Lindsay, Chris Carson, and Robert Tonyan were rostered on 7-11% of all finals teams. What mattered more was owning a top power law player like Andrews, Kupp, or Chase.

“When it comes to winning fantasy championships, UPSIDE IS EVERYTHING. Our goal when drafting should be trying to identify players with league-winning upside. A player’s bull-case projection matters much more than his base-case projection which matters far more than his bear-case projection.”

As true as those words are in a typical 12-person redraft league, they’re exponentially truer in a best ball tournament. I highly recommend reading that piece in its entirety: Upside Wins Championships.

But this is only one step in the battle. Upside is important, OK. We should be swinging for the fences with nearly every pick we make and especially in the later rounds, OK. We want to draft power law players, OK. But how can we properly identify players with league-winning upside – the top power law players like Andrews, Kupp, and Chase – ex ante?

Luckily for you, I wrote two additional articles to help:

Identifying League-Winners Ex Ante (2020) — I wrote this article looking at the top 10 league winners over the previous three seasons and showed how in almost every single case I correctly predicted their league-winning upside in the offseason. In the few cases I failed to predict a top-performing season (2017 Todd Gurley), I tried to highlight the important data points (that might have been hinting at league-winning upside) that I mistakenly overlooked.

Anatomy of a League Winner (2021) — In this article, I looked at the top league winners over the previous four seasons trying to find common threads tying these players together. I also spent some time discussing which positions were more valuable (and more conducive to producing league-winners) than others and why.

Over the next several weeks, I’ll also publish a series of articles highlighting the top values and the potential (highest-upside) league-winners in Underdog drafts.

So, again, upside is of massive importance. And as we’ve learned from DFS, there’s no simpler way to increase your upside than by correctly correlating and stacking your roster.

In a DFS cash games, stacking isn’t typically recommended. Similarly, in a traditional best ball league, stacking – though it offers positive expected value (+EV) – is a little overrated. In BestBall10s, the most optimal stack you can make (QB1+WR1+WR2) improves your odds of finishing first from 8.3% to only 9.3%, offering far less of an edge than by drafting the right number of positions. But in DFS GPPs and in best ball tournaments, stacking is of massive importance. And not only should you be team-stacking, you should also consider game-stacking in tournament rounds (Weeks 15-17, with a heavy emphasis on Week 17). More on this later.

In a traditional best ball league, Weeks 15-17 matter the same as Week 1. In a redraft league, postseason weeks matter exponentially more. Similarly, in a tournament-style best ball league, 240 points in Week 17 as opposed to Week 4 could be the difference between you making $1,000 and $2 million. So, on that point, we should be looking for players with especially favorable schedules in Weeks 15-17 (and extra-especially Week 17).

Luckily for you, I’ve written four more articles to help:

Strength of Schedule: Quarterbacks (2022)

Strength of Schedule: Running Backs (2022)

Strength of Schedule: Wide Receivers (2022)

Strength of Schedule: Tight Ends (2022)

For instance – need a tie-breaker between Jonathan Taylor and Christian McCaffrey? Well, Taylor plays the Giants (6th-worst in FPG allowed to RBs last year) in Week 17, and McCaffrey plays the Buccaneers (3rd-best over the last three seasons).

It also may make some sense to try to “get weird” and differentiate your team as much as possible. Similar to adopting a “contrarian strategy” in GPPs, the more unique your team is, the better your odds of standing out amongst a field of 451,200 teams. Hayden Winks explored this concept in more detail here.

Getting unique at the top of drafts is unquestionably +EV to me. The problem is if you have 3-4 people getting unique in the same draft you allow someone else to get unique by pairing unique 1st round player combinations. https://t.co/abWNERnoSd

— Liam Murphy (@ChessLiam) May 31, 2022

Here’s one example: Jonathan Taylor is most-frequently paired with the players being drafted around the 2.12/3.01 turn. By instead drafting players who are typically going around the 3.12/4.01 turn, you give yourself a unique pairing that stands out from the rest of the field. (At least one of A.J. Brown, Keenan Allen, or Tee Higgins may be rostered on something like 60% of Taylor teams. But Diontae Johnson may be on only a handful of Taylor teams.) So, in this instance, the cost of reaching may be offset by the increase in expected value this unique build provides.

Optimal Lineup Construction (In General)

There’s no ideal best ball strategy, nor a truly optimal roster construction. Everything is unique to your specific league type, your specific draft, and the specific season in which you’re drafting. Is it optimal to draft exactly three QBs? It depends. Who were the first two QBs you drafted? Where did you draft them? Who is still on the board? What does the rest of your team look like?

But with that being said, paying close attention to historical win rates can go a long way in maximizing an edge over your opponents.

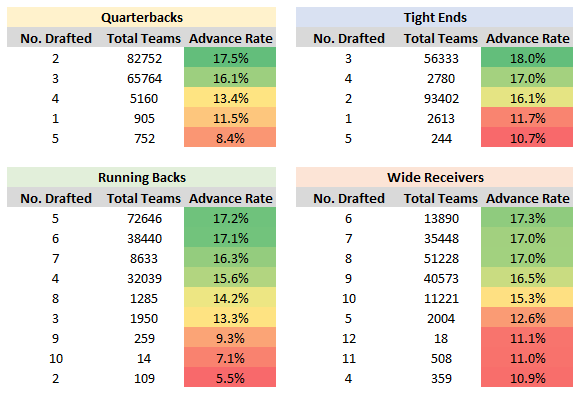

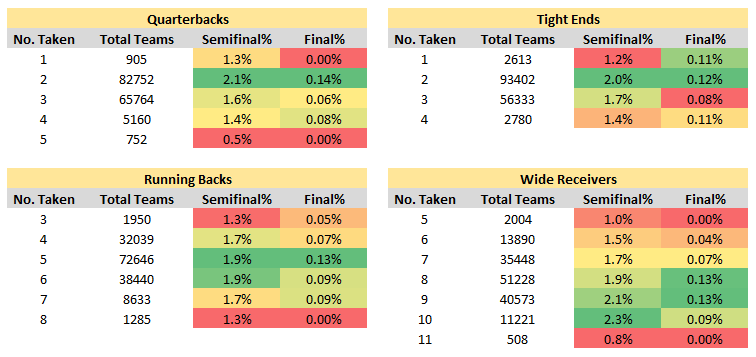

Here’s what was optimal in Underdog drafts last year (by quarterfinals advance rate):

In other words, the optimal strategy was drafting:

Quarterbacks: 2-3

Running Backs: 5-6

Wide Receivers: 6-8

Tight Ends: 3-4

Again, this is only a general guideline. If you’re drafting Travis Kelce, the optimal number of TEs is probably only two. If you’re drafting three running backs with your first three picks, you’re probably better off neglecting the position for the remainder of the draft (minus one super-late-round dart-throw).

And it’s important to note two crucial points:

1) We’re looking only at a one-year sample here, so this is probably pretty noisy. But at the same time, this is just about perfectly in line with our historical data from BestBall10s which goes back to 2015, and is not too different from Underdog’s format – minus two extra draft rounds in BestBall10s, which is mostly negated by team defense in the starting lineup, and then full-point PPR vs. half-point PPR scoring. The only real difference between our results was 7-8 WRs (vs. 6-8 WRs) and 2-3 TEs (vs. 3-4 TEs) being optimal in BestBall10s.

And I do think 2021 could have been an outlier year for TEs, and that alone could explain the discrepancy. Just about every early- to mid-range TE flopped, minus Travis Kelce and Mark Andrews. Instead, the sweet spot was Rounds 13-18 for teams that may have waited and went with a quantity-over-quality approach: Rob Gronkowski (Round 13), Dawson Knox (Round 17), Zach Ertz (Round 16), Dalton Schultz (Round 17), Pat Freiermuth (Round 16), Hunter Henry (Round 14), etc. Meanwhile, Darren Waller (Round 2), Kyle Pitts (Round 4), Logan Thomas (Round 8), Robert Tonyan (Round 10), T.J. Hockenson (Round 5), Tyler Higbee (Round 8), Noah Fant (Round 9), etc. were varying degrees of “busts” at value.

2) The methodology we’re using looks only at a team’s rate of advancing to Round 2 of the tournament (the quarterfinals). This is a fine proxy if you’re drafting in a traditional 12-team best ball league (the results are nearly identical), but does neglect three weeks of play for tournament players. This gave us our most robust sample, and everything beyond that – I felt – left us too prone to variance. But I think I’ve found an intriguing workaround, and will explore “high-upside” / tournament-winning roster constructions later in this piece.

Conditional Drafting

Just as it’s important to draft the right number of positions, it’s also important to draft the right positions in the right rounds.

The “optimal roster construction” outlined above is only optimal in a vacuum. But drafts don’t exist in a vacuum. The above approach seems optimal, but what happens if you drafted WRs with all five of your first five picks? Is eight WRs still optimal, or should you now go with 7 to provide extra support for your now ailing RB position?

This sort of thinking led Mike Beers of RotoViz to coin the term “conditional roster optimization.” He explains all of this in his own words in a terrific Twitter thread here. I’ll go ahead and give you the (paraphrased) summary, but I highly encourage you to read it in full.

So, what happens if you draft five WRs with your first five picks? Would that mean eight WRs total is no longer the optimal number of WRs to draft? Beers responds, “The answer, of course, is that the optimal construction does change based on the picks you make early in the draft. I often think of it as one of those balance scales – a RB drafted in the 2nd round clearly should not be equivalent to a RB drafted in the 12th round.” But then does a RB drafted in the 5th round plus a RB drafted in the 7th round equal a RB drafted in the 2nd round? Maybe. Good question – that’s at least the right way to think about this.

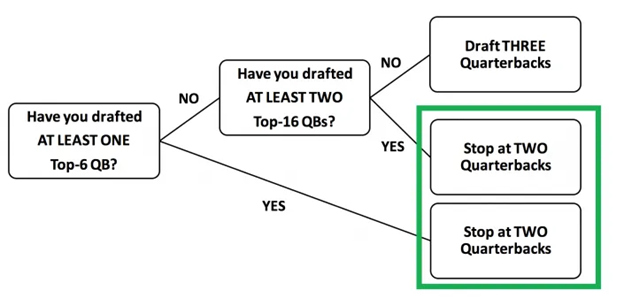

He continues, “It became clear to me that where you picked your players (how much ‘draft capital’ you spent on positions) impacted how many you should be drafting. Here's a pretty straightforward decision tree that came out of this:”

A roster needs to have balance, and one must understand the tradeoffs one is making each time they pick one position over another. “The whole thing is a balancing act between quality and quantity.” Drafting two TEs in the first five rounds means you don’t need a third, because you’re stacked at TE and can only start a maximum of two each week, and you’re also now weaker than every other team at the other positions. Conversely, punting TE until the double-digit rounds means you now have to make up for your lack of quality at the position with a quantity approach (by drafting 3-4).

Most best ball experts and pros I’ve talked to say they don’t start thinking about roster construction until after the first 5 or 6 rounds of the draft. Early on, they’ll just let the draft fall to them, and try to scoop up value where they can. But after that, roster construction surely matters a great deal, and so they’ll start looking at where they’re weak and where they’re strong. Already have four WRs? Okay, you can neglect the position for a while, and worry more about strengthening your RBs. Beers echoes that sentiment here, saying:

“The number one thing about a best ball draft strategy, to me, is that you should not go in with ‘a’ plan… you should go in with 20+ plans. At least five of them are eliminated with each pick that you make and as the balance of the roster takes shape. The real plan is flexibility, and balance. By keeping your roster balanced across positions, through quality, quantity, or a combination thereof, you put yourself ahead of the field. And then if you're really good at picking individual players, your opponents don't stand a chance and even if you AREN'T really good at picking players, you DO stand a chance. In many cases the edges from optimized roster construction are small, sure. But what a lot of people miss is that there are dozens of these edges, and they ADD UP.”

Okay, with all of this in mind, what is the “optimal” strategy at each position?

Optimal Strategy at Each Position

Notes: The positional strategies outlined below are undoubtedly optimal for a traditional 12-team best ball league on Underdog, and are probably also at least very close to optimal in Underdog’s tournaments, but we’ll go more in-depth on “high-upside” / tournament-winning roster constructions later in this piece.

Quarterback

A late-round approach at QB wouldn’t get you very far in best ball. Why? QBs are far scarcer in best ball. And because they’re scarcer, they’re more valuable.

In a typical 12-team 1QB start/sit league, we shouldn’t expect more than 16 QBs to be drafted or rostered at any given time, and, at most, 24 QBs. However, on average, we should expect 29.6 QBs to be drafted in any given Underdog draft. But, keep in mind, there were only 25 QBs to start in over 12 games last year. And today, how many QBs can we project with any level of confidence to start Week 1? And then, of those, how many might have a high risk of getting benched should they struggle after the first few weeks of the season?

This is explained in more detail here.

More or less, the optimal approach looks something like this:

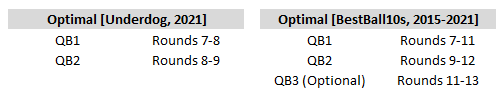

Drafting exactly two QBs from Rounds 7-9 gave you the best quarterfinals advance rate of any possible QB strategy (~20%). This is only slightly off of our recommendation when using BestBall10 data, which urges you to select your QB1 in Rounds 7-8 and your QB2 in Rounds 10-11, with an optional QB3 taken in Rounds 11-13.

If you wanted to take a third QB in Underdog drafts, you were best off taking them in the final three rounds, and only if you waited at the position and missed out on QB in the optimal rounds. But even then, the success rate was substantially less than for teams who took only two QBs and only in the optimal rounds (Rounds 7-9): ~20.0% vs. ~16.5%.

Again, the differences between the two formats was negligible, but I do think you should be drafting QBs earlier on Underdog than you would in BestBall10s. Why? Simply, QBs are more valuable in half-point PPR leagues.

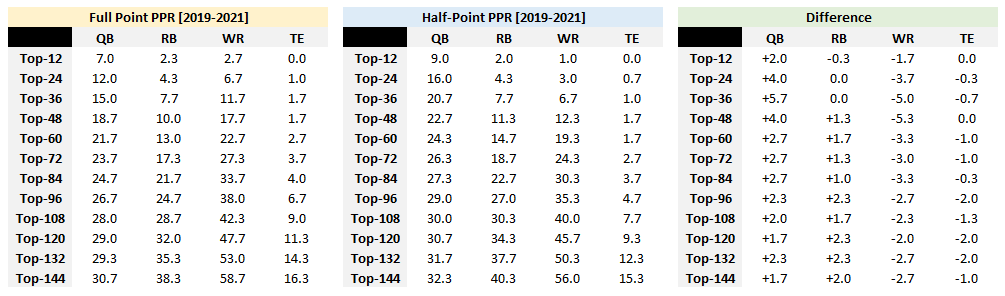

What the above chart shows is that (historically and on average) QBs make up 42% of all top-36 finishers in full-point PPR, but that jumps to 58% in half-point PPR scoring. RBs, WRs, and TEs all score fewer points in half-point PPR, which thus makes QBs slightly more valuable.

As a general rule: you don’t ever want to be the 1st or 2nd person to draft a QB, and you don’t want to draft a QB before Round 5 – historical win-rates say that’s a bad idea. And you should only ever be drafting two or three QBs in total. A good rule of thumb is something like this: If you’ve already drafted two QBs before Round 12, stop there. If you haven’t, consider three if and only if you can land one likely to be a full-season starter.

Running Back

Just like how “late round QB” loses efficacy in best ball, “Bell Cow or Bust” also loses its appeal in best ball. Conversely, “Zero-RB” (zero RBs in the first 3-4 rounds) or “Modified Zero RB” (one RB selected in the first two rounds, zero RBs over the next several rounds) becomes a far more viable strategy. Why? Because high-end RBs (but not the highest-end RBs) are simply less valuable in best ball.

A quantity over quality approach at the RB position is very much viable in best ball, while such a strategy is not at all viable in start/sit. This is explained in more detail here.

For instance, in 2020, Aaron Jones finished 4th in FPG (full-point PPR), while Nyheim Hines and J.D. McKissic both ranked only as high-end RB3s. And yet, in the best ball format (taking the higher score in each week), and if treated as one player (so, excluding all production coming in the flex), Hines and McKissic would have out-scored Jones and all but three other RBs. Meanwhile, in typical start/sit leagues, Hines and McKissic were more or less worthless as they were rarely ever started in the right weeks (their production wasn’t at all predictable).

Indeed, “a wait at RB approach” is my preferred strategy at the position, with one exception: You should still be drafting a RB with your first and/or second pick. That’s proven to be the optimal strategy in almost every instance. But after that, you should be able to afford to wait quite a while at the position, and quite a bit longer than basically all of your opponents seem to realize.

What happens if you miss out on a RB in the first two rounds? Well, that’s not very good. In either format, teams that failed to draft a RB in the first two rounds posted a win-rate well below average. In Underdog drafts last year, the gap was massive; your expected advance rate dropped from 16.7% to 10.8%. If you went this route, the data suggests you should go full-on Zero-RB, waiting until at least Round 7 to draft your first RB. And know that if you do, you should be drafting 6 or 7 total RBs, as opposed to just 5.

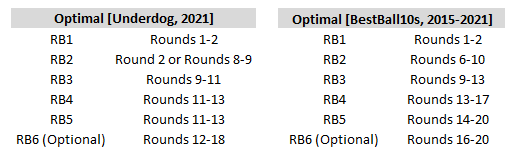

Here’s more or less what the optimal approach tends to look like:

Drafting exactly one RB through the first two rounds and then neglecting the position for multiple rounds (as the optimal approach outlined above suggests you do) is called “the modified Zero-RB” strategy. That’s long been my preferred approach in best ball, and our most robust sample of best ball data (BestBall10s, 2015-2021) suggests that this is the optimal approach. But I actually think that strategy loses some efficacy on Underdog.

The “Modified Zero RB” strategy was not optimal in Underdog drafts last year (at least in traditional 12-team best ball leagues or if measured by quarterfinals advance rate). Instead, drafting exactly two RBs in the first two rounds yielded an advance rate of 20.8%. For clarity, your next best option (and on a much smaller sample) was waiting until Rounds 8-11 to draft your second RB (18.5%-20.6%). But in BestBall10s, and over a seven-season sample, taking your RB2 in Round 2 provided only a neutral win-rate, and then a negative win-rate from Rounds 3-5.

You can argue that the difference is still somewhat negligible, or entirely skewed by Underdog’s small one-year sample size, but I don’t think that’s correct. Instead, RBs (and especially highest-end RBs) are simply more valuable in Underdog’s half-point PPR format.

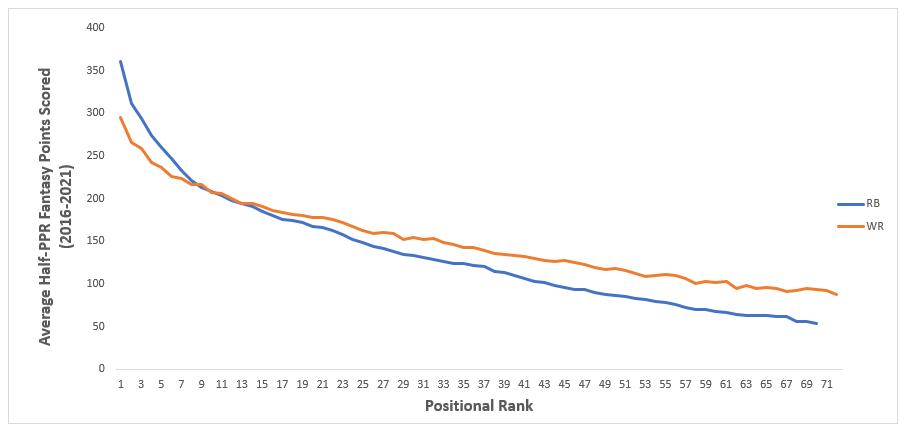

In half-point PPR scoring, RBs are 24% more likely to provide a “spike week” and thus crack your flex spot. And by year-end finish, they gain substantial ground on WRs as well.

So, in a traditional 12-team Underdog league, I’ll be aiming for two RBs in the first two rounds and then waiting at the position until Rounds 9-11 to draft my RB3. However, if there isn’t an RB2 I love in Round 2, I’m fine foregoing the position until Rounds 8-9, as the expected win-rate between the two strategies wasn’t massive. (And, as we’ll see a little bit later, a late-round RB2 approach may actually be optimal in best ball tournaments.)

Wide Receiver

Okay, so if a “wait at RB”-approach is far more viable in best ball, the next logical assumption is that WRs are also more valuable in best ball. And, well, that’s exactly correct!

And WRs are especially valuable in Underdog drafts and in BestBall10s, where you’re starting between three and four WRs each week – as opposed to FFPC which requires you to start between two and four WRs each week (same as RBs).

You’d think that because there are so many more fantasy-viable options at the WR position (in comparison to QBs, RBs, and TEs), you can get away with more of a quantity over quality approach, but the numbers don’t bear that out.

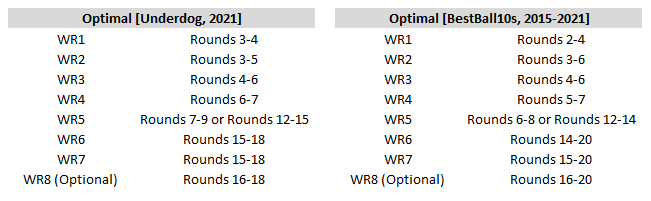

In Underdog drafts (and in BestBall10s), you should go out of your way to draft four WRs before Round 8. You can either draft your fifth WR before Round 10 or wait until Rounds 12-15 – the win rate was the same. After that, you’re better off saving your WR picks for the final three rounds.

After only the highest-tier of RBs (Round 1-2), the WR position is simply more valuable than the RB position in best ball.

For one thing, WRs generally offer a higher ceiling and, thus, are more likely to be putting up points (and more points than RBs or TEs) in your flex spot. And that’s especially true if we concede the point that highest-end RBs are more valuable than highest-end WRs. Excluding the top-3 players at both positions, last year there were 80 instances of a WR scoring at least 21.5 fantasy points in half-point PPR leagues, in comparison to only 61 RBs. Among players drafted after Round 3, WRs trumped RBs 68 to 38.

But more importantly, and more simply, after the highest tier of RBs (Rounds 1-2), WRs simply outscore RBs.

The top-8 RBs will out-score the top-8 WRs, but then things get flat, until about RB14/WR14 when WRs start to overtake RBs. And, interestingly, that implies there might be some slight value here – by current Underdog ADP, 14 RBs go off the board before the WR10 is drafted, and WRs don’t start to eclipse RBs by ADP until after the RB17/WR17 is drafted.

Tight End

TEs, like QBs, are scarcer in best ball. Because they’re scarcer, they’re more valuable.

And high-end TEs are far scarcer than high-end QBs. While QB production is fairly flat across the top 50% of the spectrum (at least historically), the TE position is far more top-heavy. On average, over the past five seasons, the TE1 outscores the TE10 by 93% in half-point PPR scoring. But The QB1 outscores the QB10 by only 36%.

So, it shouldn’t be too surprising that high-end TEs become far more valuable than high-end QBs in best ball. While that’s also true in start/sit, an added bonus in best ball is you don’t need to spend additional draft capital on a fourth or maybe even third TE, allowing you to allocate resources elsewhere. And unlike the QB position, your second TE can also contribute in the flex.

Historically – in BestBall10s – if you manage to grab one of the Big-3 TEs, you’re sitting pretty. Over the past seven seasons, drafting your TE1 before Round 5 and ending the draft with only two TEs yields an 11.1% win-rate – rivaling Modified Zero-RB (11.1-11.9%) as the best possible strategy.

If you drafted your TE1 after Round 4, your win-rate drops to either 7.6% (if you finish with two total TEs), 8.0% (if you end up with 3), or 6.0% (if you end up with 4). The best way to improve those odds – if you do miss out on one of the Big-3 TEs – is to draft three mid-to-late round TEs (9.4%). But just don’t wait too late, as the well runs dry much too fast (like with QBs, but not WRs).

But still, I’m not sure it makes sense to draft a TE in Round 1 – the opportunity cost (of losing out on a top RB or “power law” WR) may be too high. For instance, last season Travis Kelce (mid-Round 1 ADP) provided only a neutral win-rate (8.7%) in BestBall10s, below Mark Andrews (19.1%), Rob Gronkowski (13.7%), Dalton Schultz (13.6%), and 10 other names. That seems pretty low considering he scored 28% more fantasy points than the TE3. And the historical data does back this up; drafting your TE1 in Round 1 yields a win-rate well below expected (6.0% vs. 8.3%) but that jumps above 10.5% in Rounds 2 and 3.

Again, historically, the ideal strategy in BestBall10s looked something like this:

Option 1 (~11.8% win-rate): Draft TE1 between Rounds 2-4. Draft TE2 before Round 13. Don’t draft another TE.

Option 2 (~9.4% win-rate): Draft TE1 and TE2 between Rounds 8-11. Draft TE3 before Round 14. Don’t draft another TE.

In Underdog drafts last year, this optimal approach was basically this:

Option 1 (~28.5% advance rate): Draft Mark Andrews between Rounds 5 and 6. Whatever you did next didn’t really matter.

Option 2 (18.5-19.8% advance rate): Draft TE1 in Rounds 13-15. Draft TE2 in Rounds 14-15. Draft TE3 in Rounds 14-18. Optional: Draft TE4 in Rounds 17-18.

Given the small one-year sample size with our Underdog data, I’d be inclined to side with our BestBall10 data (which suggests drafting TEs earlier than in Underdog) if not for the fact that tight ends are slightly less valuable in half-point PPR. They’re slightly less valuable overall, and the talent-gap is slightly less significant between the highest-end TEs and everyone else; the lesser-tier overly-touchdown-reliant options like Hunter Henry and Pat Freiermuth make up some ground in the half-point PPR format.

But in either format, your TE strategy should be about the same: either draft the top power law player, or wait at the position and adopt more of a quantity-over-approach… But I mean, good luck predicting the 2022 version of 2021 Mark Andrews ex ante. The latter approach is only slightly less effective, but significantly less difficult. For that reason, I’ll be taking a “quantity-over-quality” approach with the position in my own (non-tournament) Underdog drafts. And instead load up on later-round TEs on high-scoring offenses with significant touchdown-upside.

But in best ball tournaments, as we’ll see a little later, high-end TEs become a far more potent asset, and should be prioritized.

Upside Roster Construction (Underdog, Smaller Sample)

I’m confident that the strategies outlined above are optimal if you wanted to avoid Underdog’s tournaments and stick to their traditional 12-team leagues…

And I’m confident the strategies outlined above are optimal for advancing to the quarterfinals of Underdog’s tournament. But what about the semifinals or finals? Or even for finishing first out of 451,200 teams?

Are there strategies that – though they may be riskier or less-optimal in the aggregate – give you more upside to finish first in the tournament? Or is the best way to increase your ceiling as simple as merely drafting as optimally as possible (as outlined in previous sections above)?

So, I crunched the numbers, shifting our approach from Underdog’s quarterfinals advance-rate to that of the semifinals or finals. To my surprise, there were quite a few interesting (and I think meaningful) takeaways:

Teams drafting exactly two TEs had a much better chance of advancing to the semifinals (2.0%) than teams drafting three (1.7%) or four TEs (1.4%), though that was the less optimal approach if measured by semifinals advance rate. In those one-week rounds it really paid off to have fewer TEs (as TEs are less likely to crack your flex-spot and don’t provide the same level of “spike weeks” when they do hit), but the right ones. Again, owning Mark Andrews was a massive cheat code, averaging 20.1 FPG over the final five weeks of the season. So, although he may be unfairly skewing our small one-season- / late-season- biased sample, I do think it might make sense that a “quantity over quality” approach raises your floor and helps you to advance to the quarterfinals (Round 2 of the tournament), but also caps your ceiling and hurts your odds of advancing further into the tournament.

Interestingly, it seems drafting only one TE may be a viable strategy for best ball tournaments, so long as that TE winds up being the No. 1 or No. 2 highest-scoring TE of the season (and ideally also in the bonus rounds). Your odds of making it to the quarterfinals and semifinals were extremely low, but the rate at which all 1TE teams advanced to the finals was comparable to the next best strategy (2TE; 0.12% vs. 0.11%). And even more curiously, this was in spite of the fact that the vast majority of those teams had Travis Kelce who scored exactly zero fantasy points in the semifinals. I worry about the small one-year sample, but I do think this makes sense a priori – having just one dominant TE may be all you need for those bonus-round weeks, while also giving you extra draft capital for the high-upside players at the positions you really want contributing in your flex-spot.

Teams drafting exactly two QBs fared much better than teams drafting 3-5 in the semifinals or finals. This was in line with our numbers when measured by quarterfinals advance rate, but more exaggerated. Again, I think this makes sense a priori. You can only start one QB, and QBs don’t contribute in the flex, so if you can make it to quarterfinals, you may only need one QB scoring a massive amount of fantasy points, while therefore also increasing your ceiling by foregoing the position later in the draft and instead drafting players contributing the flex.

And, remember, many of those dominant 2QB teams may have had Josh Allen and then a lesser-tier QB2 like Trevor Lawrence, Justin Fields, or Zach Wilson who rarely ever beat out Allen to crack their starting lineup. So, their QB2 was basically a wasted pick anyway. On that point, I suspect 1QB teams – like 1TE – teams may be a little bit more viable in best ball tournaments than anyone else seems to realize. This strategy undoubtedly hurts your odds of making it to the quarterfinals, but that may very well be offset by the upside 1QB teams offer in the tournament rounds.

Imagine owning Travis Kelce (as your only TE) and Patrick Mahomes (as your only QB). If you made it to the quarterfinals and they both finish atop their position from Weeks 15-17, you’ll have a massive advantage on the rest of the field (2-4 extra roster spots). But again, your expected quarterfinals advance rate may be far too low to make this an optimal approach. At the very least, I think this is a strategy which should be attempted more often than it was (1QB: 0.6% of all teams, 1TE: 1.7% of all teams), and the uniqueness of the approach is an added bonus.

And also, in general, but especially at the TE position (and then QB position), one simple way to increase your upside is to nearly full-on punt one position and pray you drafted the right late-round superstar. If you’re right, this could really push your team over the top – as you should be stacked everywhere else due to the savings in draft capital. For instance, last year, teams who drafted only two very late-round TEs with one of those TEs being Rob Gronkowski (ADP: Round 13), Dawson Knox (Round 17), or Dalton Schultz (Round 17) actually fared better than teams drafting Mark Andrews.

And that’s – e.g. drafting the correct late-round ADP-crushers at the position – probably the only thing that can come close to providing the same sort of value owning a top TE provides. It’s risky, and hard to accomplish, but historical ADP does suggest it happens far more often than you think, and far more often than for any other position. But in general, owning a top TE does seem to provide a massive advantage, and may very well be the optimal approach at the position. Owning a top QB is probably far less important, I think. And it’s extremely rare for a top power law player (on the level of Mark Andrews, Cooper Kupp, or Ja’Marr Chase last year) to be a QB. But I do think you need at least one QB capable of scoring 25-plus fantasy points in the tournament weeks.

At the RB position, drafting exactly five RBs was pretty glaringly the optimal approach. This was a somewhat unfortunate revelation for me, because I’ve long had a sentimental attachment to Mike Beers’ “hyper-fragile” draft strategy which recommends drafting three RBs in the first three rounds and then neglecting the position for the remainder of the draft. The thesis always made sense to me (a priori) – that the upside inherent to this strategy (three power-law bell cow RBs with zero draft capital spent at the position after that) outweighs the risk (1-3 of your RBs getting hurt), and gives you the best odds of finishing first – but the numbers don’t seem to bear that out.

At the WR position, drafting nine WRs (give or take one WR) was the optimal approach. This stands out in contrast to the numbers we cited earlier. Again, I think this makes sense a priori as well. WRs offer the most “spike weeks” at any position, and especially so at cost. And late in the season, when points matter most (in this format) is often when late-round WRs can really start to pay off (e.g. Amon-Ra St. Brown). So, if drafting in a traditional best ball league, 6-7 WRs may be optimal. But in a best ball tournament you’re going to want 1-2 WRs more than that.

I have fewer key takeaways when looking at things on a round-by-round basis, but here were the results:

Underdog 2021, Semifinals Advance Rate pic.twitter.com/uT4pkFcDwz

— Scott Barrett (@ScottBarrettDFB) June 8, 2022

Here was more or less the optimal approach (measured by semifinals advance rate) and my key takeaways:

QB1: Taking your QB1 in Rounds 1-9 was pretty clearly the optimal approach.

QB2: Taking your QB2 in Rounds 3-9 was pretty clearly the optimal approach.

(Optional) QB3: Win-rates were fairly flat across the board.

Interestingly, taking your QB1 in Round 3 (4.5%) provided the highest advance rate of any strategy. For clarity, Patrick Mahomes was the only QB last season with a Round 3 ADP (30.6 fantasy points in Week 15). And, even more interestingly, but on a much smaller sample (just 3.0% of all teams) drafting your QB2 in Round 3 (4.4%) or Round 4 (3.5%) provided the 2nd- and 3rd-best advance rates of any QB strategy. This is no doubt interesting (hinting at high-end QBs being more valuable than I had previously implied), but I worry this sample size is too small to draw any meaningful conclusions.

So, although the data seems to argue against it, I’m inclined to stick to my initial inclination. That QB2s aren’t too important. And to a lesser extent, that owning a top QB is less important than owning a top RB, WR, or TE. That a high-end QB1 is more of a luxury than a necessity. You definitely need a QB capable of scoring 25-plus fantasy points in the tournament rounds, and QBs capable of scoring 35-plus fantasy points in any week should be prioritized, but I’m not sure I see myself drafting much of Josh Allen (ADP: Round 3). (However, Kyler Murray in Round 6 is an entirely different story.)

And the ancillary data does seem to support this notion a little better, with Round 8-9 QBs Aaron Rodgers, Matthew Stafford, Joe Burrow, and Jalen Hurts winding up on a similar percentage of finals teams to Patrick Mahomes (ADP: Round 3) and Josh Allen (Round 4), who both ranked outside of the top-10 highest-owned players overall.

Best Ball Mania II (2021) Finals Ownership% pic.twitter.com/2MsjsORAeo

— Scott Barrett (@ScottBarrettDFB) June 11, 2022

RB1: Round 2.

RB2: Round 2 or Rounds 7-12 or (small sample warning) Rounds 7-16.

RB3: Rounds 9-13.

RB4: Rounds 10-14.

RB5: Rounds 11-18.

(Optional) RB6: Rounds 14-18.

Interestingly, and in stark contrast to the numbers we cited earlier, teams taking a RB1 in Round 1 fared much worse (1.4%) than teams which drafted their RB1 in Round 2 (4.3%). (Though teams taking their RB1 in Round 1 saw their odds dramatically improve if they also took their RB2 in Round 2.)

Taking your RB1 in Round 2 was far-and-away the optimal approach last year (by semifinals advance rate), faring much better than the 2nd- and 3rd- most optimal rounds for a RB1 (Round 10 and Round 12), which also had a near-infinitesimally small sample. If not taking your RB1 in Round 2, taking them in Rounds 6-10 was probably your next best strategy.

Notes: 2021 was a down-year for Round 1 RBs, and Week 15 was also an especially weird week. Obviously, teams with Round 1 RBs Derrick Henry and Christian McCaffrey were already out of contention at this point. But also, among the top-20 highest-scoring RBs of the week, we find names like: Duke Johnson (RB1), Jeff Wilson (RB3), James Robinson (RB4), Devin Singletary (RB6), D’Onta Foreman (RB11), Ameer Abdullah (RB13), DeeJay Dallas (RB14), Sony Michel (RB15), Craig Reynolds (RB17), Justin Jackson (RB18), and Tony Pollard (RB20). So, clearly we need to be wary of small sample bias, and one weird week (where RB1s atypically underwhelmed compared to late-round randos) skewing our results. Though, it’s also true – giving credence to a Zero-RB or Modified Zero-RB strategy – that later-round RBs tend to be more productive later in the season (due to injuries)… But, on the whole, teams drafting their RB1 in Rounds 1 or 2 made up 86% of all drafted teams and 84% of all finals teams. So, that doesn’t necessarily strike me as a suboptimal approach.

Indeed, Zero-RB may not be optimal, but it is, I think, a far more viable strategy in best ball tournaments than in typical start/sit redraft leagues or standard best ball leagues. And Modified Zero-RB may actually be the optimal RB strategy.

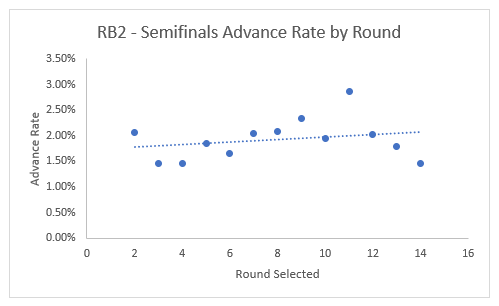

Remember, when measured by quarterfinals advance rate, taking your RB2 in Round 2 only barely edged out (20.8%) taking your RB2 in Round 9 (20.6%). If measured by semifinals advance rate, teams taking their RB2 before Round 7 advanced only 1.8% of the time. But teams waiting until Round 11 or later, advanced 2.5% of the time.

And by finals advance rate, the results were significantly more dramatic – 0.22% versus 3.98%. Our sample size was extremely small here, with only 2.3% of all teams waiting until Round 11 or later to draft their RB2. That’s a slight concern, but more than anything, I think this means that such a strategy is under-represented, highly unique, and should be attempted more often than it was last year.

So, in my own tournament drafts, I’ll try to attempt only three RB strategies, ending with usually five total RBs in each instance:

Strategy 1 (~50% of my drafts): Modified Zero-RB – one RB in the first two rounds, then try to wait until (at the earliest) Round 9 for my RB2. (Maybe draft an RB2 earlier than that, but only if he’s a massive ADP faller.)

Strategy 2 (~25% of my drafts): Zero-RB – avoid RBs for at least the first five rounds.

Strategy 3 (~25% of my drafts): Two RBs in the first two rounds and then try to wait at the position until (at the earliest) Round 9 for my RB3. (Maybe draft an RB3 earlier than that, but only if he’s a massive ADP faller.)

To recap, the main differences in this section were Round 2 RB1 trumping Round 1 RB1 by advance rate, and how insanely flat RB2 advance-rates were by round (with only a very slightly positive trendline implying the later you selected your RB2 the better). (See below.)

Again, this could be due solely to our extremely small and then one-week biased sample, but otherwise these results are just about perfectly in line with what we’ve found in the previous sections.

WR1: Round 1 or Rounds 3-7.

WR2: Rounds 7-11.

WR3: Rounds 8-11.

WR4: Rounds 8-11.

WR5: Rounds 9-13.

WR6: Rounds 11-15.

WR7: Rounds 13-16.

WR8: Rounds 14-18.

(Optional) WR9: Rounds 15-18.

(Optional) WR10: Rounds 15-18.

We discussed earlier that drafting your WR1 in Round 1 was suboptimal, but those odds greatly improved if measured by semifinals advance rate. This supports the notion we just spoke of, that a Zero-RB or Modified Zero-RB strategy may offer more upside and, thus, viability in best ball tournaments. However, the greatest difference overall was that (when measured by semifinal advance rate) you could afford to take your WR2, WR3, WR4, and WR5 much later (3-5 rounds later) in each instance. But again, I worry about the small sample size, and how Week 15 juggernauts like Tyreek Hill, Cooper Kupp, and Brandin Cooks may be heavily influencing our results.

TE1: Round 1 (4.1%) or Rounds 5-6 (4.4-4.6%)

TE2: Rounds 5-6.

(Optional) TE3: Rounds 5-7.

(Optional) TE4: Rounds 12-18.

Again, it seems everything came down to drafting Travis Kelce in Round 1 or Mark Andrews in Rounds 5-6. Kelce scored 36.1 fantasy points in Week 15, and Andrews scored 30.6. Without one of those two players, your hit-rate is at best one-third of what it would have been with Kelce or Andrews. And, interestingly, owning both seemed to be an even more potent cheat code, providing a whopping 12.7% semifinal advance rate (up from 8.8% if just owning Andrews).

The data suggests that drafting a top-5 TE is an immensely potent and likely optimal approach if you want a top team. And I do think that’s true for best ball tournaments; your odds of making it to the quarterfinals may be better with a “quantity over quality approach”, but you really need those “spike weeks” from your TE in the one-week rounds.

As for whether or not owning two top-5 TEs may be even more optimal, I’ll explore this at greater length in the section below.

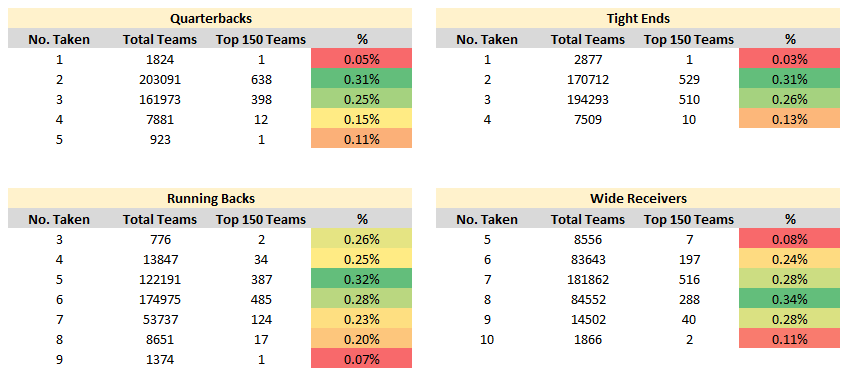

Upside Roster Construction (BestBall10s, More Robust Sample)

Again, I worry about the small (one-season biased / late-season biased) sample size with Underdog’s data, so I wanted to take this a step further and dig into the seven-season sample BestBall10s offer. So, I looked only at the top-150 BestBall10 scorers in each season (of about 51,600 total teams in each season). Here was, more or less, the optimal approach:

Total QBs: 2 (Most Optimal: 2) Total RBs: 5-6 (Most Optimal: 5) Total WRs: 7-9 (Most Optimal: 8) Total TEs: 2-3 (Most Optimal: 2)

So, just about perfectly in line with what we found when looking at each league’s first place finisher.

But now here’s where things get a lot more interesting – looking at each position by draft round:

BestBall10s (2015-2021)

— Scott Barrett (@ScottBarrettDFB) June 8, 2022

+ Top-150 Teams (of ~51,600 total teams) in each season

H/T: @beerswater pic.twitter.com/bQE5DjoggF

Here was more or less the optimal approach and my key takeaways:

QB1: Taking your QB1 in Rounds 5-10 was pretty clearly the optimal approach. (Most optimal: 7-9).

QB2: Taking your QB2 in Rounds 9-11 was pretty clearly the optimal approach. (Most optimal: Rounds 10-11).

(Optional) QB3: Win-rates were fairly flat across the board. (Most optimal: Rounds 13-15).

This is just about perfectly in line with the results we found earlier. But in half-point PPR formats like Underdog, you may still want to bump QBs up a round or two.

RB1: Round 1-2 or (small sample warning) Rounds 6-8.

RB2: Round 6-8 or (small sample warning) Rounds 6-12.

RB3: Pretty flat across the board from Rounds 6-15, but if we forgive the small sample, it seems the later you draft your RB3 (so long as it’s before Round 16) the better.

RB4: Pretty flat across the board after Round 11, but if we forgive the small sample, it seems the later you draft your RB4 the better.

RB5: Rounds 15-20.

(Optional) RB6: Rounds 18-20.

Again, it seems that a Zero-RB approach (and especially a Modified Zero-RB approach) becomes far more viable when you’re looking for a top-0.3% outcome (finishing top-150 out of ~51,600 total teams).

At the very least, it’s clear you’re better off drafting your RB2-RB5 a lot later than your fellow leaguemates seem to realize. But also, please remember, highest-end RBs do tend to be more valuable in half-point PPR leagues – so maybe not your RB2 so late. But with that in mind, I do think these results solidify my preferred 50%/25%/25% RB strategy I outlined earlier.

WR1: Rounds 3-4.

WR2: Rounds 4-5.

WR3: Rounds 4-6.

WR4: Rounds 5-7.

WR5: Rounds 7-9 or (slightly less optimal) Rounds 12-14.

WR6: Rounds 12-16.

WR7: Rounds 14-17.

WR8: Rounds 14-20.

(Optional) WR9: Round 19-20.

As we said earlier with WRs, “You should go out of your way to draft four WRs before Round 8.” And that’s glaringly the case here as well.

So, with BestBall10s – at every position we’ve explored thus far – the ideal “upside roster construction” is pretty closely in line with the ideal roster construction if merely aiming to finish first in a 12-team league.

The only difference between the results here and those when measured by Underdog semifinals advance-rate is that a “quality over quantity” approach seems to serve you a bit better in BestBall10s. But I’m inclined to believe that this – “quality over quantity” – should be the preferred strategy in Underdog’s half-point PPR format as well, though I think I may still try to draft a ninth WR in the majority of my Underdog tournament leagues.

TE1: Round 2-3, otherwise fairly flat across the board before Round 15.

TE2: Round 3-4, otherwise extremely flat from Rounds 7-20.

(Optional) TE3: Pretty flat across the board, except if we forgive the extremely (extremely) small sample, Rounds 7-11 seems weirdly optimal.

Okay, now things get interesting. It really seems as though – if you want a truly dominant (top-0.3% team) – you really need to land at least one power-law TE. And maybe landing two is even more optimal, as we alluded to earlier.

This reminds me of an extremely old article, at the dawn of best ball strategy content, which recommended drafting two TEs in the first four rounds as the optimal approach. And I think it does make some sense a priori as well – it increases your odds of landing at least one power law TE, later round WRs are better values with more upside, you don’t need to spend any additional capital on a third TE, your second TE can contribute in the flex, etc. If the two TEs you’ve drafted are putting up WR1-levels of production (2021 Travis Kelce + Mark Andrews, 2020 Travis Kelce + Darren Waller), this could indeed be a massive cheat code.

I think, based on the data and given how (rare and) unique this approach is, it’s certainly worth attempting or experimenting with in Underdog tournament drafts, though it may lose some efficacy in Underdog’s half-point PPR format.

But also, if I can push back on this narrative just a little bit, I will say that TE has historically been one of the best positions to find value (and even power law players) extremely late – George Kittle (2018), Eric Ebron (2018), Mark Andrews (2019), Darren Waller (2019), Logan Thomas (2020), Robert Tonyan (2020), Dalton Schultz (2021), Rob Gronkowski (2021), etc.

Team Stack

In a traditional 12-team best ball league, stacking is somewhat overrated. In a best ball tournament, just like in DFS GPPs, stacking is of massive importance.

Obviously, it increases your ceiling – the top power-law WR in any given week (which is also typically the top power-law player in any given week) is usually catching passes from the highest-scoring QB of the week. And, often enough, the highest-scoring QB of the week is capable of supporting multiple high-scoring pass-catchers – like in Week 1 of last season when Tom Brady finished as (merely) the overall QB5 (29.2 fantasy points), but Rob Gronkowski (25.0), Antonio Brown (21.2), and Chris Godwin (19.0) finished as the TE1, WR9, and WR13 of the week.

But also, it makes things easier on you in terms of roster construction.

In DFS, JMtoWin is always preaching that you should think about constructing your tournament lineup like you would picking a lock. Instead of trying to get all 9 roster spots perfectly correct, if you’re properly utilizing stacks, you may only need to get 5 things right. (e.g. “I think New England dominates the Jets in a run-heavy blowout. I think CIN@HOU is the highest-scoring game of the week, and a pass-heavy shoutout. So, I’m going to roster: Damien Harris + New England DST, and Davis Mills+Brandin Cooks+Ja’Marr Chase+Tee Higgins. And if I’m correct, now I only need to nail my other three roster spots – RB2, TE, Flex.)

And the data is clear – in Underdog tournaments, the more stacked players you had (or the fewer unstacked players), the better your odds of advancing to the quarterfinals.

You should be looking to stack a good chunk of your BBM3 players.

— Chris Wecht (@ChrisWechtFF) June 8, 2022

Results from BBM2 clearly show advance rates for the regular season favored players stacked with at least one other teammate (min 500 drafted teams) pic.twitter.com/ndDocmnJji

Obviously, the most obvious and most common team stack is pairing your QB1 with his WR1. But in Best Ball Mania, the bigger the stack, the better.

Stacking was a clear edge in BBM2 and the bigger the stack the better pic.twitter.com/ULNkfC4prT

— Chris Wecht (@ChrisWechtFF) February 28, 2022

Which is to say, you shouldn’t just stop there (QB1+WR1). You should also consider drafting the team’s RB1, WR2, WR3, and TE1. For instance, I imagine it would have been impossible to win the Best Ball Mania contest in 2018 (had it existed) without all of the following players on the Kansas City Chiefs: Patrick Mahomes (Round 11, QB1 finish), Travis Kelce (Round 3, TE1 finish), Tyreek Hill (Round 3, WR1 finish), Kareem Hunt (Round 6, RB11 finish in 11 games).

Similarly, owning five (46%) or six players (52%) on the Buccaneers gave you the best odds (and coin-flippish odds overall) of making it to the quarterfinals last year.

However, Hayden Winks looked at the data and pushed back on this narrative here, suggesting instead the optimal approach consists of “one mini stack and a bunch of one-offs, particularly one set of two teammates, two sets of two teammates, or one set of three teammates." With the most positively correlated stacks consisting of a QB1 with his WR1, WR2, and/or TE1.

Other less frequently utilized stacks like QB1+RB1 (who is ideally a pass-catching RB) or WR1+RB1 do also provide a slightly positive correlation (and also uniqueness to your build), but just nowhere near as high of a correlation as a QB plus his primary pass-catchers.

After reading through Winks’ article and then sifting through the data myself, I think a three-to-four player stack is probably optimal, but five or more could be beneficial if you’re really confident in a team massively exceeding ADP-based expectations (like the 2018 Chiefs or 2021 Buccaneers).

And in general, the cheaper a stack is, the more upside there is, and probably the more unique it is. For that reason, among others, I continually find myself gravitating towards Daniel Jones-stacks in Underdog tournaments. Jones is cheap (ADP: QB23, Round 15), has rushing upside, has a massively upgraded supporting cast (receivers, offensive line, and, crucially, coaches), is bound to see a massive uptick in pace of play, has historically provided spike weeks at one of the highest rates at the position, has the league’s most-improved strength of schedule, and the league’s best postseason schedule. And his WRs have the league’s 2nd softest playoff schedule at the position, and are all cheap as well – Kadarius Toney (ADP: WR49), Kenny Golladay (WR57), Wan'Dale Robinson (WR81), and Sterling Shepard (WR97). All of this is explained in more detail here and here.

But there’s no question that getting sniped on your ideal QB hurts you in the one-week bonus rounds.

Is your team dead if someone snipes your QB from your main stack in Best Ball?

— Chris Wecht (@ChrisWechtFF) March 1, 2022

Turns out your team still has basically the same advance rate out of the regular season but you might be in big trouble in making it to the Finals in Best Ball Mania pic.twitter.com/UJdWqrCSgg

So, for instance, if you’ve already drafted Ja’Marr Chase and Tee Higgins, it may be worth reaching a full round on Joe Burrow… But, then again, maybe not. As now you’ve ceded a full round in draft value to the teams who were able to let the Burrow-stack fall naturally to them. So, alternatively, maybe instead try to turn your team stack into a gamestack by drafting one of the opposing QBs [along with their WR2] that Burrow will be playing against in the tournament weeks.

Last year’s Best Ball Mania II winner – Liam Murphy (@ChessLiam) – actually won the tournament while rostering Ja’Marr Chase and Tyler Boyd without Joe Burrow.

If you’re curious what the winning team of @UnderdogFantasy’s BBM2 scored in the regular season it’s posted below.

— Liam Murphy (@ChessLiam) May 18, 2022

If you have any questions ask away pic.twitter.com/pKlkOXg1H8

In general, the less your WR1’s QB runs, the more you’d want to stack him with his QB. The more they run, the less necessary it is to stack them, or the less receivers you’d want to pair them with. But also, if you miss out on your WR1’s QB, you can go the route Liam did and instead prioritize hyper-mobile “Konami Code QBs” who are capable of out-scoring that QB in spike weeks with just their legs (and without any of their receivers going off).

Last year's winning roster (@ChessLiam) utilized three team stacks and two separate Week 17 game stacks

— TJ Hernandez (@TJHernandez) May 18, 2022

One game stack combined for 60.5 fantasy points and two players from team stacks combined for another 74 points

You may also notice that Murphy didn’t have a high number of team stacks, but he did have a few Week 17 gamestacks. And that wasn’t at all by accident. Murphy told us on a recent livestream that he placed a high level of importance on Week 17 matchups and gamestacks. And his overall strategy (paraphrased):

“There’s two theories of thought here. One theory is: I want to advance as many teams as I can into the finals and then hope I get lucky from there. But the other is, and it’s how I built my teams last year, was with first place in mind. It was, how do I make an amazingly high-upside team?”

Elsewhere he explained, “The urge to advance in best ball is so rooted in our minds that even sharp players play sub-optimally… Personally I don't care about the advance rate of an individual player on my roster. I mainly build for the highest upside Week 17 case I can make.”

Game Stack

Again, if we’re thinking of best ball tournaments the same way we would DFS tournaments (and we should) we should consider utilizing playoff round (and especially Week 17) game stacks in addition to team stacks.

For instance, in Week 8 of 2015, NYG@NO provided us with the overall QB1, QB2, RB6, RB9, WR1, WR5, WR9, WR10, WR17, and TE1 of the week. Had this came in Week 17, undoubtedly the $2 million-winning team in Best Ball Mania (had it existed at that point) would have been whichever team still remaining had the most Saints and Giants players.

your mom and literally me pic.twitter.com/aeOV50dVsk

— Scott Barrett (@ScottBarrettDFB) June 3, 2022

Game-stacking should only be considered in tournament weeks, with a heavy emphasis on Week 17 (and then maybe, to a lesser extent Week 16).

My initial thought was that you probably shouldn’t ever force a game stack; instead, merely prioritize one player (with a gamestack) over one without if they’re nearly tied or at least within the same tier according to our rankings.

I was thinking along these lines:

“Well, I already have Travis Kelce stacked with Patrick Mahomes. I should definitely try to grab one of Marquez Valdes-Scantling or Skyy Moore a little later. But who do they play in Week 17? OK, they’re up against the Russell Wilson-led Denver Broncos. That could definitely be a high-scoring pass-heavy shootout. I’m about to be on the clock in two picks here in Round 5. Although I have Gabriel Davis slightly ahead in my rankings, I should probably take Jerry Jeudy or Courtland Sutton for the stack, and maybe also Albert Okwuegbunam or Tim Patrick a little later as well.”

But then again… I mean, you could get really weird with it. Really try to push the limits of this strategy, like Murphy was encouraging us to on our livestream. For instance, if you think LAR@LAC is the highest scoring game of Week 17, and those teams are both a bit undervalued by ADP, you could go all-in drafting: Justin Herbert (Round 4) or Matthew Stafford (Round 8), Cooper Kupp (Round 1), Keenan Allen (Round 3), Mike Williams (Round 4), Allen Robinson (Round 5), Tyler Higbee (Round 13), and/or Gerald Everett (Round 15). That would give you an extremely unique build with massive Week 17 upside.

Remember, if one player drops 40.0-plus fantasy points in Week 17 (like Ja’Marr Chase did last year), and you don’t own that player, you’re not going to finish in 1st place. And with Best Ball Mania’s top-heavy payout ($2 million to 1st place, $10,000 to 11th place) your goal should be finishing 1st. Hence why we should put so much importance on Week 17.

As for which gamestacks are most potent, I encourage you to read this piece by Brandon Gdula, using FanDuel’s scoring system (which is the same as Underdog’s). (Hayden Winks also examines this data in the article we linked to earlier.) But in general, the most highly correlated opposing team game stacks are:

QB1+Opposing WR2 WR2+Opposing QB WR2+Opposing WR2 WR3+Opposing QB WR3+Opposing WR2

So, a really potent game stack could look something like this: QB1+WR1+WR2+Opposing WR2

Tournament TLDR

UPSIDE IS EVERYTHING.

The fewer unstacked players you have on your team the better.

Place an extreme, heavy emphasis on Week 17 matchups and gamestacks.

My personal positional strategy in Underdog tournaments:

QB: At least one QB capable of 25-plus or (ideally) 30-plus fantasy points in the tournament weeks. QB2 will be whoever fits my team stack or Week 17 gamestack and isn’t as important. I usually won’t be drafting a QB3.

RB: Drafting, usually 5 RBs in total, following the 50%/25%/25% strategy I outlined earlier.

WR: A “quality plus quantity”-approach. Usually nine WRs in total, with four WRs drafted before Round 8.

TE: Try my best to land the top TE at the position, and then not really sweat my TE2. But also occasionally try to experiment by drafting two alpha TEs. If I miss out on a TE1 with alpha-potential, I’ll full-on punt the position with two high-upside TEs late. In any approach, I won’t often draft a TE3.

Other: I may try to allocate something like 10% of my exposure to 1QB and/or 1TE builds, with those players always being drafted in the first few rounds of the draft.

Other Important Tips

1. The optimal draft strategy when it comes to picking individual players (as opposed to individual positions) is something like what I described here. Use our best ball rankings and site ADP in tandem. If we have one player really high, but he’s a lot lower by ADP, you should draft him later. That way you get more value and give yourself an even bigger edge.

2. If you’re going to be drafting a high number of teams, make sure you’re paying close attention to ADP and are frequently grabbing the big ADP values when they fall. This will help bring down the average cost across all of your drafts, which is highly beneficial to your portfolio of teams. And, for tournaments, it also adds to the uniqueness of your roster – for instance, I may hate Cam Akers at his ADP (Round 4), but I’d be ecstatic to grab him in Round 7 solely because I may be only one of a handful of teams to draft him so late.

3. If you’re going to be drafting a high number of teams, it’s important to diversify the players you’re taking, especially early in drafts. The most profitable best ball players I’ve talked to, all say they only take extreme hardline stands in final rounds of their drafts (where, in some cases, 80% exposure or more is fine). If those late-round players flop it doesn’t really hurt you, but that is the optimal time to be drafting for upside and swinging for the fences with your picks – a Round 16 WR was unlikely to crack your starting lineup more than once or twice anyway. Among players in the single-digit rounds, best ball pros are unlikely to ever have less than 5% exposure or more than 25% exposure to any individual player. Here’s a great example why:

In 2020, Travis Kelce posted the highest win-rate in BestBall10s. If you drafted him, you won 24.4% of the time. If you drafted Saquon Barkley, you won 0.3% of the time. That’s an unreal difference – Barkley hurt you more than any two players might have helped you. Kelce improved your odds by a magnitude of 3X, Barkley hurt them by a magnitude of 28X.

4. Once again, UPSIDE IS EVERYTHING in best ball tournaments. Really try to prioritize upside with every pick you make, and especially in the later rounds.

For instance, I think Rob Gronkowski (ADP: Round 10) and Antonio Brown (Round 18) are ideal tournament picks at current ADP. Sure, there’s a chance neither player even plays a game of football this year. But in this format (where you want to finish 1st of 451,200 teams) their upside is far more valuable than their downside risk is detrimental.

5. On that point, remember: “Certain players are more valuable in best ball… In a best ball league, week-to-week consistency doesn’t matter nearly as much as a high weekly ceiling.”

Top-30 Most Valuable Players in @UnderdogFantasy's Best Ball Mania (2021)

— Scott Barrett (@ScottBarrettDFB) June 3, 2022

Left: Quarterfinals Advance Rate (into Round 2 of the tournament)

Right: Finals Advance Rate (into Final Round of the tournament) pic.twitter.com/Wk7FNejnrw

Jake Tribbey will publish a series of articles at a later date, highlighting the most- and least-consistent players in fantasy. Or in other words, the players who are better suited for best ball versus typical start/sit leagues. But here’s an example:

Last season Jakobi Meyers out-scored Russell Gage by 38.3 fantasy points (+27%). And even though Gage was also 2.5 Rounds more expensive by ADP, he still bested Meyers by BestBall10 win-rate (11.3% vs. 10.3%). Why? Because Gage offered the higher weekly ceiling, and thus, he was in your starting lineup far more often than Meyers, and when he was in your starting lineup, he was scoring more points. Gage had three games with at least 22.0 fantasy points, but Meyers never hit that mark even once despite playing in three additional games.

Meyers’ consistency made him more valuable in start/sit leagues (where he did beat Gage by win-rate), but his lack of ceiling made him less valuable in best ball. Those are the sort of players you’re going to want to avoid in best ball leagues, while prioritizing players that offer a higher weekly ceiling. A player who is a borderline liability in start/sit leagues could be a best ball superstar.

For instance, Tyler Lockett will always rank higher in our best ball rankings than in our start/sit rankings. Over the past three seasons, he averages 36.5 FPG in his three best games each year. Across his other 39 games (81% of games), he averages just 11.4 FPG (~WR46).

6. And, on that point, make sure you’re thinking about how certain players pair well with others (beyond just stacks).

Aging veterans like Rob Gronkowski can be trusted to put up points early in the season, but then start to wear down, dealing with injuries or declining in efficiency. So, perhaps an ideal TE pairing with Gronkowski would be someone like Greg Dulcich, as TEs are significantly more productive in the second-half of their rookie seasons. Similarly, a DeAndre Hopkins (suspended for the first six games) may pair best with an injury-prone or aging veteran WR (like Adam Thielen), or one with an especially soft schedule to start the year.

Or, if you drafted three RBs with your first 4-5 picks, a Tony Pollard might make more sense as your RB4 than a Nyheim Hines. Even if Jonathan Taylor were to suffer an injury, it’s hard to imagine Hines producing much more than his typical 6-12 fantasy points. And 6-12 fantasy points shouldn’t ever be beating out the three RBs you drafted in the first five rounds. So, in this instance, it would make more sense to eschew a high-floor RB4 and chase Pollard’s upside instead (20-plus points if Elliott were to miss time).

7. Getting autopicked a poor player who doesn’t fit your roster construction can crush your odds of winning, so avoid that at all costs. For that reason, when doing multiple drafts simultaneously, I prefer to enter only slow drafts (8-hour clock) and set a timer on my phone to go off every 5.5 hours.

8. Your most profitable month is likely going to be August, when all of the fish have come out of hibernation and start drafting QBs in Round 1. But February through April won’t be too far behind, before the ADP is set and then refined. And especially not too far behind if you’re a fan of college football and know who all the best incoming rookies are. (Luckily for you, even if you’re not, Wes Huber’s articles, my rookie Draft Guide, and the Fantasy Points NFL Draft Guide with Greg Cosell's prospect evaluations are always here to help.)

Drafting the right rookies before the NFL Draft (when they’ll become far more expensive) is a massive edge. Players like Alvin Kamara, James Robinson, Justin Jefferson, Kareem Hunt, Saquon Barkley, Terry McLaurin, and many others were all massive league-winners in their rookie seasons. And they provided more value to you earlier on when they were discounted by sometimes 5-10 rounds. I’ve discussed this in more detail here, as has Mike Beers here.

For instance, last year in early March, I wrote this: "Wes Huber thinks Amon-Ra St. Brown is an ideal late-round draft pick in best ball and a borderline Round 1 talent (NFL Draft). And I might like Elijah Moore from a Year 1 perspective even more. Both are currently going undrafted in 90% of all BestBall10 leagues."

But typically, you want the bulk of your drafts to come either as early or as late in the offseason as possible. Last year’s Best Ball Mania winner Liam Murphy referred to this as the “barbell approach” on our recent livestream.

9. You probably don’t want to be the first or second person to draft a QB in best ball. The historical win-rate there isn’t very good. But if you’re going to, you should do it earlier in the year. High-end QBs are cheap only up until the fish come out and start overdrafting them. I talked about this here, alongside the point that mid-tier RBs are at their riskiest and least-valuable prior to free agency and the NFL Draft.

10. Bye weeks are overrated. You can use byes to break ties, and especially when you’re only drafting two players at a position, but for the most part that’s something the pros don’t even really look at.

11. In both traditional 12-team best ball leagues, and especially in best ball tournament leagues, handcuffing is a proven minus-EV strategy. Whereas a positively correlated stack increases your ceiling at the cost of your floor, handcuffing provides the opposite effect. It’s simply a too costly insurance policy given the payout structure. Mike Beers discussed this in more detail here.

But drafting a backup RB without drafting that player’s RB1 can increase your ceiling. Backup RBs and those sorts of players (high-upside, low median projection) are especially valuable in best ball tournaments. And, with backup RBs in particular, they do tend to post their best games in the final weeks of the season (as injuries start to add up).

For instance, Alexander Mattison is probabilistically a minus-EV pick, only cracking your starting lineup in the 1-2 games Dalvin Cook misses. But if Cook were to miss a dozen games or more, or even just Week 17, he could be one of the most valuable players in the tournament. Mattison has exceeded 12.0 fantasy points in just six of 42 career games (14%). But he’s also averaged 20.1 FPG in the six games Cook has missed. So, if this (albeit unlikely) outcome comes to fruition, you not only landed a potential power law player in the double-digit rounds (a massive advantage), but you’ve gained an edge on a large number of your opponents, as all 451,200 Dalvin Cook owners are now drawing dead in the tournament.

12. Quickly re-hashing some key points from Anatomy of a League-Winner, which, again, you really should read…

Broadly speaking, in a typical ESPN 10-team start / sit league: "High-end running backs are worth roughly 2.2X as much as high-end wide receivers, which are worth roughly 1.7X as much as high-end tight ends, which are worth roughly 1.2X as much as high-end quarterbacks." Things change when switching the focus to best ball, but not by much. A top-3 WR or especially a top-3 RB is still going to be exponentially more valuable than a top-3 QB.

ADP is least predictive at the QB position.

The three most valuable players in any league are typically RBs. And the top power-law RBs are typically only found in Rounds 1-2.

League-winning WRs are typically only found at the top of your draft (Rounds 1-6) or all the way at the bottom (UDFA).

The safest position to punt while still having decent odds of landing a league-winner is undoubtedly the TE position – George Kittle (2018), Eric Ebron (2018), Mark Andrews (2019), Darren Waller (2019), Logan Thomas (2020), Robert Tonyan (2020), Dalton Schultz (2021), Rob Gronkowski (2021), etc.

12. After reading all of the previous 12,000 words in this article, you might think that the optimal approach in Best Ball Mania III would look something like this:

Round 1: RB1

Round 2: TE1

Round 3: WR1

Round 4: WR2

Round 5: WR3

Round 6: WR4

Round 7: QB1

Round 8: RB2

Round 9: QB2 Round 10: WR5 Round 11: RB3

And, well, maybe that’s sort of right. But the best players I talked to don’t think about the game in this way. Instead, they let the draft fall to them for the first 5-6 rounds, and then start worrying about roster construction. I think Mike Beers put it best when he said: “You should not go in with a set plan… you should go in with 20+ plans. At least 5 of them are eliminated with each pick that you make and as the balance of the roster takes shape. The real plan is flexibility, and balance.”